By Jeff Kosovich & Stephanie Wormington

Often, the impact of leadership development is synonymous with return on investment (ROI) or Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). How does leadership development help organizations meet their bottom line, and are leaders satisfied with their development experience? But what happens in leadership development programs that contributes to positive ROI? Much like the real world, there is no one simple answer. Dozens-perhaps even hundreds-of actions, thoughts, and contexts make up the steppingstones on leaders’ development journey that support their organization’s overall ROI. With so much happening, where can we begin in understanding the full impact of leadership development?

In this post, we focus on a powerful belief that applies in nearly every life domain: Confidence. Before you roll your eyes, close the tab, and search for cute cat pictures, this is not a treatise on the power of positive thought or “if you believe it, you can achieve it!”

Broadly, confidence is the answer to the question of “can I do this?” where “this” can reference anything as small as logging in to your work computer or as large as deciding the strategic direction for your organization. More specifically, confidence is the expectation that an individual or group can achieve some task, goal, or outcome. You may have heard of self-efficacy 1, growth mindset 2, expectations for success 3,4, or a panoply of other terms from academic or popular press sources. Regardless of its specific flavor, confidence can develop during leadership development experiences and is a critical ingredient to leaders’ success.

Center for Creative Leadership (CCL)® has collected data from leaders across the globe—from grade school children to executive-level leaders—who hold many different positions and social identities. Together, these insights suggest that confidence matters for the betterment of leaders, groups, organizations, and society worldwide.

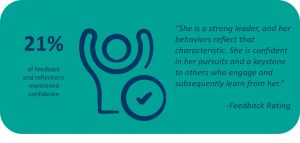

Insight 1: Confidence is a visible indicator of leadership development.

One of CCL’s partner programs is designed to develop individual leaders from diverse professions who want to improve health and equity. The program is a multi-year experience and includes leaders from early career through retirement. Approximately 40 new leaders are inducted into the program annually and receive a 360-degree assessment with data from a group of their coworkers during the beginning, middle, and end of their program. Based on feedback from 210 raters for one cohort of leaders, more than one fifth of responses mention greater confidence from the leader as an area of growth. This provides evidence that confidence can be developed because of leadership training opportunities.

Insight 2: Increased leadership confidence repeatedly ranks as a major area of change in college students.

In another partnership with the Golden LEAF Scholars Leadership Program, 80-120 students every year join a four-year leadership experience for incoming college freshmen. The goal is to build leadership skills and work with the scholars to identify promising career paths in rural and economically distressed communities. At the beginning and end of each program year, CCL collects data on multiple short-term outcomes. Across five cohorts (2016-2020), scholars reported increased leadership confidence as among the top three most developed skills each year, increasing an average of nearly one full point (+ 0.82 points) on a seven-point rating scale. Importantly, in the graph below, the three complete cohorts (2016-2018) have the largest change, whereas the two in-progress cohorts (2019 & 2020) have substantially less change. This insight suggests that confidence consistently improves over time.

Note: ‡ Data from 2016 – 2018 represent completed cohorts. 2019 and 2020 represent scholars who most recently completed their 3rd and 2nd years, respectively. Error bars represent +/- 2 standard errors.

Note: ‡ Data from 2016 – 2018 represent completed cohorts. 2019 and 2020 represent scholars who most recently completed their 3rd and 2nd years, respectively. Error bars represent +/- 2 standard errors.

Insight 3: Confidence and support play a role in Gen Z and Millennials’ desire to pursue leadership positions.

Confidence can also be a precursor to pursuing leadership positions in the first place. In a recent partnership with Y20 (the youth arm of the G20), more than 10,000 young adults ages 18-35 from 20 countries shared whether they were interested in pursuing a leadership role and why (or why not).

Their responses suggested that confidence was important for becoming a leader and feeling effective in a leadership position. Of the 3,000+ respondents who currently held leadership positions, most felt empowered in their role. Nearly three-quarters (73%) felt confident that their voice was heard, 65% were confident they could make decisions on their own, and 90% felt they had a positive impact on their organization or community. Compared to aspiring leaders and non-leaders, current leaders (especially those who felt empowered) were more likely to have received support from their parents or other important adults encouraging them to become a leader. This insight suggests that leadership plays a part in pursuing and persevering in leadership roles.

Note: Values represent the percentage of current leaders who agreed or strongly agreed with each statement.

Note: Values represent the percentage of current leaders who agreed or strongly agreed with each statement.

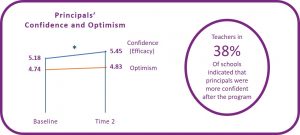

Finding 4: K-12 More confident principals (as described by themselves and others) report higher retention rates and greater resilience.

Confidence also plays an important role in school settings. The Margaret Waddington Institute for School Leadership is focused on supporting and developing K-12 principals in the state of Vermont. To date, nearly half (n = 129) of all Vermont principals have participated in the experience over the past several years.

One of the noteworthy changes during the program is that the principals reported increased confidence (but not optimism) at the end of the program. These same principals also reported stable, rather than increasing, levels of burnout and were more likely to remain in their position than principals who did not participate in the program. These concurrent changes suggest important connections between increasing confidence and some of the most important outcomes in education settings (in this case, burnout and retention). It also highlights that a change in confidence is not the same as a change in optimism.

Note: *Change in confidence was statistically significant (p < .05). Results are from a group of 77 principals across 7 cohorts of Vermont principals. Confidence was mentioned in 38% of the 61 schools that participated in the program.

Note: *Change in confidence was statistically significant (p < .05). Results are from a group of 77 principals across 7 cohorts of Vermont principals. Confidence was mentioned in 38% of the 61 schools that participated in the program.

So what?

From community activists to principals, our findings suggest that confidence is a consistent indicator of leaders’ success. It plays a role in the decision to pursue leadership roles, and it plays a role in remaining in a challenging career. These insights align with decades of research that confidence (as a proxy for self-efficacy, expectations for success, psychological capital 5,6, growth mindset, and other concepts) is one of the strongest predictors of achievement. It means that greater confidence may precede more far-reaching impact 7.

With these insights, we return to our point at the beginning of this blog and highlight confidence as a major outcome of leadership development preceding or alongside KPIs. The distinction between confidence and optimism from Insight 4 also highlights that confidence requires more than a positive attitude; instead, we need to consider the different factors that promote strong, positive confidence.

Now What?

We have shared findings indicating that confidence is important and malleable. What can leaders do to bolster their own and others’ confidence? Research1 suggests four key sources of change:

- Experiencing success in the past: one of the greatest indicators of whether you are confident in being able to complete a task is if you have lived experience of having successfully completed it before. This can include simulated experiences as low-risk stepping stones.

- Seeing others being successful: having concrete evidence of others successfully completing a task can boost your confidence in being successful yourself, particularly the more similar those others are to you (e.g., shared social identities, skills, or past experiences). This can include mentoring from experienced leaders.

- Receiving support from others: the more important people in your life have confidence in you, the more likely you are to have confidence in yourself. This can include receiving constructive feedback, like from a 360 assessment.

- Feeling like you will be confident: your body sends you physiological and emotional signals that you interpret as being confident, nervous, unsure, or a range of other states. The more you interpret your racing heart as excitement (versus stress), the more likely you are to believe in your ability to succeed.

In a future post, we will dive deep into some of the stories of how our partners and programs have created solid foundations for confidence. However, we know that every person, context, and leadership experience is unique. How can you support these sources of confidence in your own work, with your team, or among your greater organization and communities?

References

1 Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Macmillan, New York.

2 Kouzes, T. K., & Posner, B. Z. (2019). Influence of managers’ mindset on leadership behavior. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(8), 829-844. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-03-2019-0142

3 Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859.

4 Lloyd, R., & Mertens, D. (2018). Expecting more out of expectancy theory: History urges inclusion of the social context. International Management Review, 14(1), 28-43.

5 Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2015). Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford University Press, USA.

6 Gorgievski, M. J., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2008). Work can burn us out or fire us up: Conservation of resources in burnout and engagement. Handbook of stress and burnout in health care, 2008, 7-22.

7 Khorakian, A., & Sharifirad, M. S. (2019). Integrating Implicit Leadership Theories, Leader–Member Exchange, Self-Efficacy, and Attachment Theory to Predict Job Performance. Psychological Reports, 122(3), 1117–1144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294118773400