By Mike Raper

As evaluators, we are often asked how we decide what to evaluate, or how. Well, for me, it’s a matter of maximizing my own contributions by evaluating the things that we believe have the most impact on leaders. One of those is the evaluation of leadership coaching. Research abounds on the effectiveness of coaching; you can find books and articles on it by the truckload, and coaching is its own industry around the world. And anecdotally, everyone in the business “knows” coaching has an impact. The bigger question is how does it have an impact? What specific attributes of leadership can we say coaching is impacting, and at what level?

Methods and Sources of Data

To address this question we need data from two groups measured on the same variables, but under two conditions; one group that participated in coaching, and one group that didn’t. Part of many Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) programs is integrated coaching, where the coach and participant continue to meet post program on their own schedules. This is typically for two sessions, included as part of the program experience, but it is not mandatory; the participant determines when the sessions take place and whether to do them at all. Our goal was to find out if this additional post-program coaching was providing any impact.

We also wanted to get data from more than one perspective, because triangulation is always the best approach. One source is good, but multiple sources are better! So we used two sources – survey data from the participants themselves, and manager data from a 360 assessment.

Since post program coaching isn’t mandatory, that gave us our two groups; those that chose to do their coaching, and those that didn’t. We couldn’t use random assignment, so we had to use a quasi-experimental method of comparison for both these data sources.

Comparison One – Post Program Impact Self Report

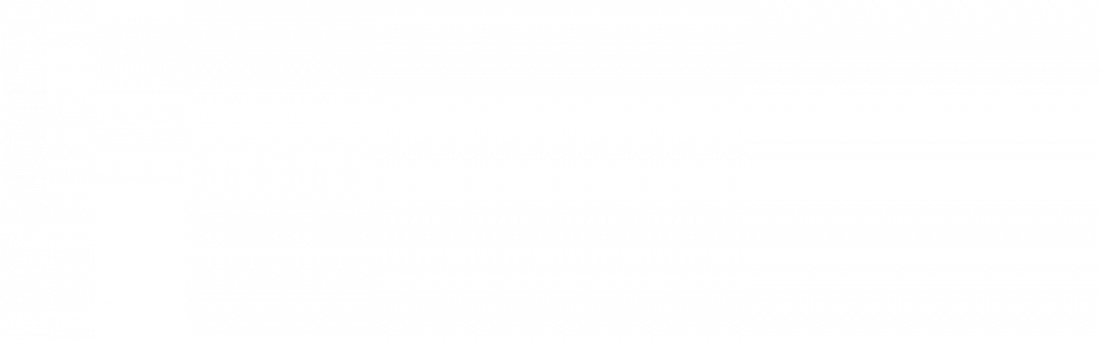

CCL sends an impact survey to our program participants eight weeks after their program is over. Within that survey, they are asked if they connected with their coach post program. Of 5504 participants, 78% of them said “yes”. So, we compared all the participants who said “yes” those that said “no” on 19 different items related to program impact, measured on a 1-10 Likert extent scale (not at all to a very great extent). A sampling of these items is listed in Figure 1, but we were surprised to find that in all of these 19 items, participants who connected with their coaches reported higher scores than those that did not.

In addition, in every case, the differences were significant with a p value of less than .01 and with moderate Cohen’s effect sizes. Or put simply, the differences are highly likely to exist in any sample drawn from this population of participants, and the presence of coaching is an important factor in that difference.

In addition, in every case, the differences were significant with a p value of less than .01 and with moderate Cohen’s effect sizes. Or put simply, the differences are highly likely to exist in any sample drawn from this population of participants, and the presence of coaching is an important factor in that difference.

What Else did We Find?

While this is good data, it’s all self-report data…the information only comes from the participants themselves, and while that’s valuable, it’s better if we can get other rater information. And there’s no better source of information about the effectiveness of coaching on a participant than their manager. Other than the participants, the managers have the most invested in the results of the coaching. They help determine what a coaching participant’s goals would be.

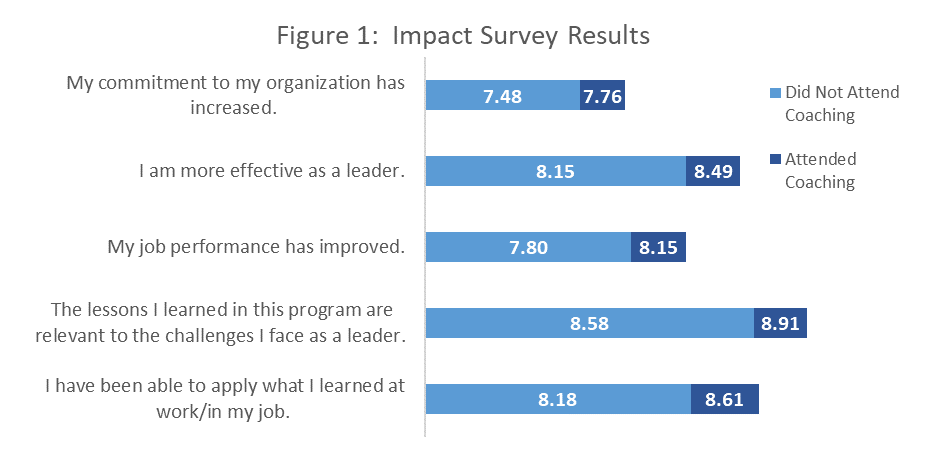

We could answer this question of manager opinion by looking at Reflections®, a retrospective 360 assessment we use several weeks post program. Reflections is often taken after the participant in a program has initiated or even completed their post-program coaching, and it includes manager feedback about the participant’s performance pre- and post-program…so it is an ideal way to see if coaching has any impact on the manager’s perceptions.

Our Reflections data includes 685 participants where coaching was an option. 91% of those did participate in post-program coaching. Like the impact survey data, we found that there were differences in those participants who did attend coaching and those that did not.

Reflections measures 11 individual impact items, rated by the manger, as well as 10 organizational impact items on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 – Significantly Decreased or Worsened to 5 – Significantly Increased or Improved. In all 21 of these items, participants who attended coaching were rated higher by their managers than those that didn’t. Figure 2 shows another sample of these items and the differences coaching is contributing.

Limitations

Limitations

We find that employees who state that they are more committed to their development are also more likely to engage with coaching post-program. So it is possible that these improvements are influenced by the fact that these participants are already potentially more engaged than average. However, the data still clearly shows that in every item those that complete their coaching score higher, both with their own ratings, and among their managers. So coaching does have a significant, positive relationship with better outcomes, but without further study, we cannot be certain it is a causal relationship.

Conclusion

Given these findings, it seems very clear that coaching makes a difference in not only the individual development of the participants, but in their impact on the organization as well. The combination of applying what is learned in the classroom with the post-program individual attention from a coach who’s helped you understand your assessments and worked with you on your challenges can improve your investment in your program experience.