By: Marcia A. Dawkins and Daniel J. Smith

Succession planning—deciding who leads next, who steps aside, and how complex organizational systems adapt under pressure—has always been a focal point for storytelling. From Shakespearean dramas like King Lear to today’s television series like Shōgun and Industry, this theme transcends generations, shaping how we think about power, leadership, and legacy. Yet, the “overstory” of succession planning—the set of underlying cultural narratives that quietly influence our understanding—often highlights conflict and hierarchy while overlooking collaboration and pluralism.i

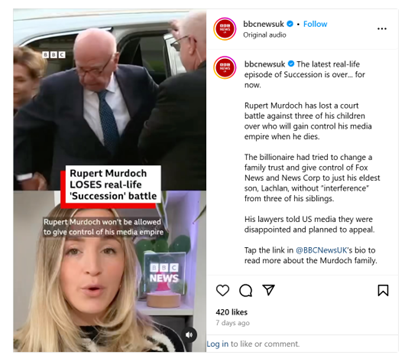

Recent headlines demonstrate just how much this overstory spills over into real life. Take these as examples: Rupert Murdoch loses bid in real-life ‘Succession’ battleii or Real-life ‘Succession’: What is the latest Murdoch family drama all about?iii or The latest real-life episode of ‘Succession’ is over… for now.iv

News and social media outlets are focusing on the legal complexities surrounding the Murdoch family trustv and the impact of television’s Succession on the family’s decision-making.vi Succession and its real-world influence reveal the fragility of leadership transitions; especially those that grapple with the vagaries of family politics, governance, and long-term vision.

This intersection of art and life inspired us to pose the following questions:

What do we know about succession planning from media representations? And why does that knowledge matter?

Our analysis of 161 Emmy and Golden Globe-nominated TV shows from 1970 to 2023 explores how succession planning is portrayed in some of the most acclaimed television narratives.vii From Breaking Bad to The Crown to Succession, we noted a sharp rise in media storytelling around leadership transitions and that these stories reflect deeply held beliefs about power and control.

Demographics: The Man-Centered Overstory

The data speaks volumes. Of the 161 Emmy and Golden Globe-nominated TV shows we analyzed, protagonists who identify as men dominate succession narratives, making up 79% of central characters. Protagonists who identify as women, in contrast, account for only 6%, while 15% of succession stories center on mixed gender teams or are simply undefined.

This imbalance frames leadership transitions as a man’s domain, often leaving women-led narratives to explore themes such as undermined authority and glass ceilings. This reality is also depicted in news and industry articles, which report that women lead only 10.4% of Fortune 500 companiesviii and that they experience significant and unseen challenges along the way.ix Shows like Veep, The Crown, The Good Wife, and The Morning Show disrupt these norms as their seasons progress but begin with the burden of proving women successors deserve to lead. In contrast, leadership potential is often assumed in man-led narratives like The Gentlemen. This dynamic reflects broader workplace patterns: men are more frequently hired or promoted based on their potential while women are judged on their experience and proven track record.x The absence of pluralistic storytelling limits our imagination of what leadership can and should look and sound like.

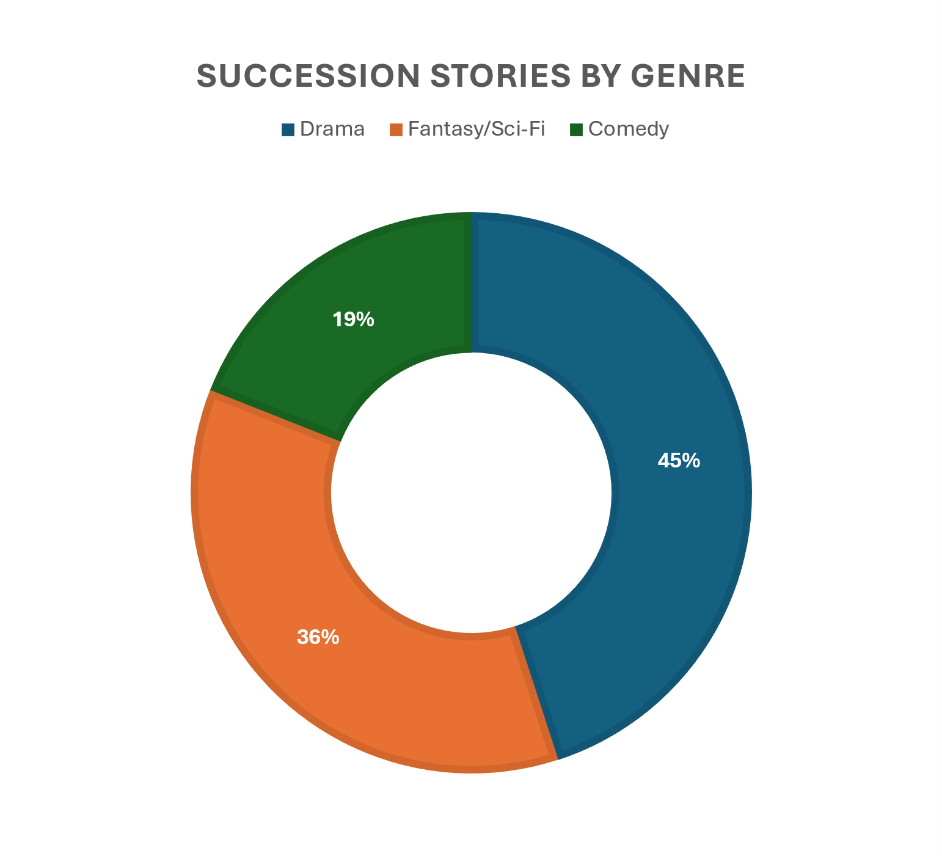

Genres: Where Drama Dominates, Fantasy Innovates, and Comedy Correctsxi

Succession planning themes thrive in Drama (45%), where family feuds and corporate conflicts drive emotional storytelling. Shows like Dynasty, The Associates, and Empire showcase the high stakes and personal toll of leadership transitions.

Meanwhile, Fantasy/Sci-Fi (36%) emerges as an unexpected secondary space for succession planning narratives. From the power struggles of Game of Thrones to the legacy-building in Star Trek, these genres use imaginative settings to reframe succession planning as an expansive, multigenerational opportunity.

Comedy (19%) provides a corrective lens, with shows like Arrested Development poking fun at the chaos of leadership transitions in family firms while shows like Ted Lasso offer alternative visions of mentorship, advocacy, and collaboration.

What TV Gets Right—and Wrong—About Succession Planning

Television’s portrayal of succession planning reveals three dominant norms:

- Succession Planning is a Negative Experience to Avoid… Unless You Like Trouble

Conflict, betrayal, and instability dominate the overstory in drama and sci-fi/fantasy, as current leaders neither step aside willingly nor give their “blessing” to the next generations. While compelling, this framing perpetuates fear and mistrust, so audiences have a hard time seeing succession as an opportunity to enact a collaborative, systemic process involving sponsorship, advocacy, and collective growth. We did find notable exceptions, including Yellowstone and Star Trek. These shows portray succession planning as the necessary and deliberate preparation of emerging leaders through developmental relationships.xii In so doing, they make room for more constructive depictions of conflict as part of a purposeful succession process that balances legacy with long-term sustainability. - Succession Planning is a Manly, Senior Leadership Problem

Stories across genres often focus on preserving elite power structures, rarely exploring pluralistic or unconventional settings. Think Dallas or West Wing. As noted above, stories rarely feature women leaders, leaders from unconventional backgrounds or leaders in small-scale settings. Few narratives explore identifying junior talent or nurturing unconventional successors. Ted Lasso is a rare example that breaks this mold by showing how the AFC Richmond Greyhounds, a woman-owned and led sports organization, creates space for successfully developing new and unconventional leaders. But even Ted Lasso’s success was not initially expected by those who chose him for the job. This plot twist illuminates key cultural factors of effective organizational transformation and succession planning that are often overlooked. - Succession Planning is Seen in a Vacuum

Shows like Succession and Dynasty favor the “romance of leadership”xiii approach of praising or blaming leaders for results over addressing systemic issues like socioeconomic disparityxiv and governance challenges in the biggest of companies. Research tells us succession planning is just one of several factors that impact an organization’s successes or failures. Recent economic studies reveal only 12% of the original Fortune 500 companies from 1955 remained in 2020,xv highlighting capital structure and market valuation as equally critical to long-term survival.xvi By playing up the romance of individual leaders and leadership styles, the overstory diverts attention from connecting succession to broader societal and macroeconomic trends.

Why Media Matters

Media representations matter because they help shape our perceptions of leadership, ultimately influencing how organizations approach succession planning in the real world. The majority of stories available about succession planning teach us to fear transitions, to preserve the status quo, and to prioritize short-term fixes over long-term vision. For leaders and organizations, these ways of thinking can generate critical blind spots.

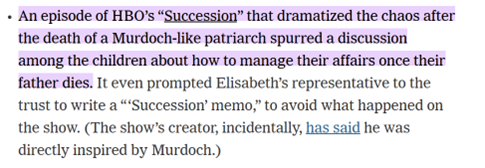

Returning to the Murdoch family’s recent succession planning challenges as discussed by mainstream news outlets (not to mention TikTok), we can begin to see these media effects in action. Communication research explains how “the bundle of objects and attributes conveyed by the media often become the bundle of objects and attributes that people have in their minds and conversations.”xvii Take the following excerpt from the December 10, 2024, New York Times article titled, How Rupert Murdoch Could Fight Back After a Big Legal Defeat:xviii

To be precise, the episode that inspired the “Succession memo” was number seven, Too Much Birthday, from season three.xix And in a recent interview on Jimmy Kimmel Live, Succession actor Jeremy Strong (Kendall Roy) noted that media storytelling has the power to reveal emotional truths about real people in real-world leadership situations that, if faced, can guide real-world change. “I’ve been accused of taking it seriously, and I do take it seriously,” Strong said. “It,” in this case, is the overstory of succession planning being written in real-time by media representations.xx

Leaders, regardless of industry or role, must understand the overstory and reconceptualize succession planning as more than a biased, crisis-driven process that exists in a vacuum. Succession planning is a leadership development opportunity. One that requires the courage to communicate through conflict, the agility to drive short- and long-term results, the patience to exercise emotional intelligence, and the foresight to ensure the next generation of leaders is equipped to thrive in a brittle, anxious, and non-linear world.xxi Zooming out, succession planning is about the power to shape organizational systems and the broader cultural overstory.

Our Takeaway for Leaders

Our analysis shows the urgent need to confront the facts and fictions of succession planning. This need is supported by increasing demand for effective succession planning across industries from news and entertainment to agriculture to pharmaceutical and medical products. Moreover, the narrow norms shaping the current overstory in top television series are only one chapter of the full succession planning narrative. Industry signals and research literature in leadership development and talent management write the next chapters, which both confirm and amend the overstory uncovered in our analysis. The prevalence of these additional data points suggests leaders can benefit from taking a more comprehensive approach to understanding the full range of political, cultural, and relational factors at play.

Succession planning is, to quote Succession’s patriarch/CEO Logan Roy, for “serious people.” And the serious decisions and transitions it entails should inspire trust, innovation, and shared purpose; qualities that resonate far beyond the boardroom. Shifting the narrative to embrace new and different succession stories can help ensure this serious work is portrayed with the depth and nuance it deserves, while connecting it to the larger forces shaping organizations and their futures.

i Gladwell, M. (2024). Revenge of the tipping point: Overstories, superspreaders, and the rise of social engineering. New York: Little, Brown & Company.

ii https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c2ld084z8jjo

iv https://www.instagram.com/bbcnewsuk/reel/DDaeTGcK23q/

v https://www.theguardian.com/media/2024/dec/09/rupert-murdochmedia-empire-children

vi https://deadline.com/2024/12/jeremy-strong-succession-rupert-murdoch-family-talks-1236200440/

vii Our data set included 349 Emmy and Golden Globe nominated TV shows from 1970-2023. We coded plots for “Succession planning,” which was defined as preparing for the future by developing people for key roles and building an organizational legacy. First, succession planning was identified in the plots, which yielded 161 TV shows. Specific questions about being an outgoing or incoming leader were included, as well as general information about gender demographics. Our confidence in categorizing gender is high (we demonstrated a .88 correlation between our coders’ judgments and the gender status of actors playing characters in media content). Animal, robot, and supernatural creature characters that were not depicted as human-like were not sorted into any category for gender and are excluded from analysis.

viii https://fortune.com/2024/06/04/fortune-500-companies-women-ceos-2024/

ix https://hbr.org/2013/09/women-rising-the-unseen-barriers

xi We relied upon several sources of information to determine genre distinctions: Variety Insight, IMDB, and Box Office Mojo.

xii MCall, M. W., Lombardo, M. M., & Morrison, A. M. (1988). The lessons of experience: How successful executives develop on the job. New York:Free Press.

xiii Meindl, J. R., Ehrlich, S. B. & Dukerich, J. M. (1985). The romance of leadership. Administrative Science Quarterly. 30(1): 78-102.

xiv Ingram, P. & Joohyun Oh, J. (2022). Mapping the class ceiling: The social class disadvantage for attaining management positions. Academy of Management Discoveries 8(1). https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2020.0030

xv Xie, W. (2024). Capital structures of surviving Fortune 500 companies: A retrospective analysis for the past seven decades. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 21(1), 98-115. doi: 10.21511/imfi.21(1).2024.09

xvi https://fortune.com/ranking/future-50/

xvii McCombs, M. & Valenzuela, S. (2021). Setting the agenda. Medford: Polity Press. p. 72.

xx One way to explain the increasing public interest in succession planning and its overstory is agenda setting theory. Agenda Setting Theory is about how the media can shape what we think is important. It works like this: when the media, such as blockbuster series or news outlets or social media, repeatedly cover a certain topic, it signals to the audience that this topic is significant. For example, if the news constantly reports on CEOs’ leadership transitions, people might start to see succession as a top priority, even if there are other important issues going on in organizational life. The theory suggests that the media doesn’t tell us what to think, but rather what to think about. Over time, media coverage can influence public opinion and even what topics are addressed by senior leaders, boards, politicians or in public policies. Essentially, Agenda Setting Theory shows how the media plays a key role in focusing our attention on certain issues while other topics may be overlooked.

xxi The BANI model, developed by futurist Jamais Cascio, offers a framework for understanding our modern world through four key characteristics: Brittle (easily broken systems), Anxious (pervasive fear about the future), Non-linear (disproportionate cause-effect relationships), and Incomprehensible (complexity beyond full understanding). This model builds upon the earlier VUCA framework, providing a more nuanced lens for navigating today’s complex challenges. In the context of succession planning, BANI underscores the need for developing resilient, adaptable leaders who can thrive amidst uncertainty and rapid change, making it a valuable consideration for organizations preparing their next generation of leadership.

https://medium.com/@cascio/human-responses-to-a-bani-world-fb3a296e9cac