Encouraging leaders to attend a leadership development program is a lot like sending them off to a training camp.

Athletes typically attend training camps hoping to hone new skills, but if you’ve ever participated in a sport, you’ll know the real development happens when they return. It’s necessary to practice those new skills, especially during competitions, games, or matches, to ensure they’ll stick. In fact, athletes who lose out on the chance to use their skills in the context in which they’ll have to rely on them, like a competition, may even get frustrated and plead for a chance to apply what they’ve learned by being put in the game.

All learning and personal growth requires time and experience, which means leaders, like athletes, need opportunities to practice and expand on their new skills once they return from “camp”. Unfortunately, organizations investing in leadership development often fail to provide the post-program support that would help leaders transfer new skills and insights to their role,1 2 and this may come at a cost.

At the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL), we’re invested in delivering leadership development programs that have a positive, long-term impact. Based on past research, we know that manager support plays a large role in whether our participants continue to improve.3 However, compared with other forms of post-program support, we wondered what factors play the largest role in the continued development of CCL’s program participants.

In this blog, we explore the extent to which different types of support from our participants’ organizations impacts their self-reported level of improvement after participating in our programs.

Organizational Support Matters for Leadership Improvement

We turned to CCL’s post-program impact survey, titled Return on Leadership Learning, to investigate what kind of organizational support has the biggest impact on participant leadership improvement. Based on CCL’s Leadership Development Impact (LDI) Framework,4 this survey is administered to participants eight weeks after their program ends and includes a section of questions about participants’ organizational support (summarized below).

On a response scale from one (“No Extent”) to five (“Very Great Extent”), to what extent do you:

- Receive developmental support from your manager?

- Receive developmental support from your peers?

- Receive organizational support for your development goals?

- Have opportunities to apply your new skills at work?

We wanted to know how the answers to these four questions relate to participants’ perceived improvement of their leadership effectiveness. To do this, we needed to find a way to capture participants’ improvement on key leadership development outcomes.

We identified eight additional Return on Leadership Learning survey questions measuring improvement in the participant’s individual effectiveness as a leader as well as their impact on their team and organization. We then combined participant responses to these eight questions into one composite score that captures whether participants generally reported higher or lower perceived leadership improvement at the individual, team, and organizational level. In this post, we’ll refer to this score as the Perceived Leadership Improvement (PLI) score.[i]

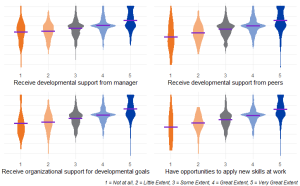

With perceived leadership improvement as our outcome of interest, we then looked at how PLI score distributions differed based on the four organizational support variables for our sample of over 2,300 leaders. When we plotted the distribution of PLI scores across levels of organizational support, we found a general increasing trend as support grows.

CCL leadership development participants who report higher levels of each kind of organizational support tend to experience higher levels of leadership improvement than those who don’t.

Note: Each violin plot shows the distribution of participants’ perceived leadership improvement scores. The mean score (depicted by a purple line) increased as their responses describing their levels of organizational support shifted from “Not at All” to “Very Great Extent”.

Comparing Organizational Support Variables

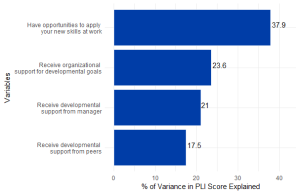

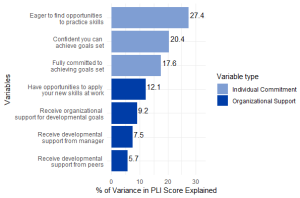

Our next step was to explore how closely related the different types of organizational support were to perceived leadership improvement. One metric we used to answer this question was the percent of variance explained, which tells us how much the variation in PLI scores can be attributed to the change in our four organizational support variables. These four variables together explained about a quarter of the variance in participants’ PLI scores. However, an analysis of the relative importance of each variable showed that one stands out more than the rest: opportunities to apply learning.

Although support from managers and peers is important, our model suggests that the most impactful form of organizational support is the extent to which leaders receive opportunities to apply their new skills at work.

Note: The percentages are out of the 24% of variance in PLI scores explained by our four organizational support variables. They were calculated using Relative Importance Analysis.5

These results align with research in the learning and development space, which shows just how important opportunities to apply skills are for post-program transfer of learning.6 The importance of learning through experience is also reflected in CCL’s 70-20-10 Model,7 which indicates about 70% of executive development comes from opportunities for on-the-job experiences.

While leadership development programs often have immediate benefits, like energizing leaders and helping them feel more engaged, providing developing leaders with opportunities to use and expand their new skills following the program will have an even larger impact.

Organizational Support vs. Individual Commitment: The Story Is Clearer When We Consider Both

Organizational support is just one influence among a multitude of factors that impact the effectiveness of leadership development in organizations. We wondered whether our organizational support variables would still explain differences in perceived leadership improvement when we also considered varying levels of leaders’ personal commitment to their own development after the program’s end.

The Return on Leadership Learning survey captures individual commitment in three questions.

On a response scale from one (“No Extent”) to five (“Very Great Extent”), to what extent do you agree that you have been…

- Fully committed to achieving the goals you set?

- Confident that you can achieve the goals you set?

- Eager to find opportunities to practice the skills you learned?

We created a new model to predict PLI score based on the four organizational support variables and the three individual commitment variables described above. Results showed that the new model increased in explanatory power from about 25% to 40%, meaning the differences in perceived leadership improvement were explained better when individual commitment and organizational support were considered together. The individual commitment variables held the most weight in the model, and after that, the most informative organizational support variable was participants’ opportunities to apply what they learned at work.

While individual commitment is very important for improving leadership effectiveness, organizational support is also highly valuable, especially giving employees opportunities to practice their skills.

Note: The percentages are out of the 40% of variance in PLI scores explained by the seven organizational support and leader commitment variables, combined. They were calculated using Relative Importance Analysis. 5

It seems obvious that when individual commitment to development is low, a person’s developmental outcomes may suffer as a result. Yet we suspected that when individual commitment is high, organizational support for development may have the most impact.

So, does the impact of organizational support depend on leaders’ individual commitment?

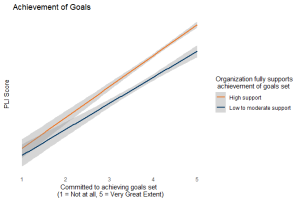

We found that the most powerful predictor of perceived leadership improvement was the combination of leaders’ commitment to achieving goals and organizational support for the same.

As the graph indicates, when commitment to achieving goals is low, organizational support has a moderate impact on perceived leadership improvement. But when commitment is high, organizational support for achieving goals has a much larger impact. In other words, leaders who are committed to development have higher payoffs when they’re put in the game and supported along the way.

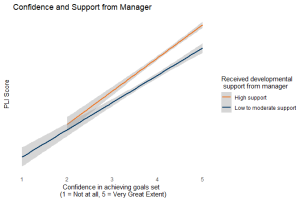

We found a similar combined effect of a leader’s personal confidence in their ability to achieve goals and developmental support from managers.

Managerial support enhances or minimizes the effect of leaders’ personal confidence on their perceived leadership improvement. When a leader is less confident in their ability to achieve goals, support from their manager will not go very far. However, those who have higher levels of confidence will improve even more when they also receive developmental support from their manager. These results once again highlight the important role managers play in developing their direct reports.8

Maximizing the Impact of Leadership Development

What can organizations do to make sure their leadership development investments have lasting impact?

In general, organizations should strive to provide intentional support for leaders’ development goals, by creating opportunities for leaders to practice their new skills and by tapping into leaders’ networks to ensure they have the support they need. We have two concrete suggestions for accomplishing this goal.

- Staff projects and organizational initiatives in a way that will foster the development of new leadership capabilities.

Provide opportunities for leaders who recently learned new skills to head task forces, committees, or project teams. Many times, employees don’t have the chance to be active players in the game and practice leadership skills relevant to their role. Organizations often move quickly and tap people in their ‘go-to’ network of contributors who they might know to be reliable. Not only can that practice result in burnout for the few chosen, but it also results in a lack of opportunities for new talent and leadership to emerge.9 By purposefully staffing these opportunities with leaders who will get the most benefit from using their new skills, not only will you develop the leader, but you’ll also improve the organization’s collective thinking by bringing new wisdom into spaces where decisions are being made. It’s a win-win for all!

- Leverage leaders’ professional and peer networks to bolster continued learning and support through mentorship, coaching, and sponsorship programs.10

Although peer support played a lesser role in our model than other variables, leveraging professional and peer networks can boost leadership learning in ways some organizations may not always consider. Our results showed that support in a leader’s network, from both managers and peers, can affect leadership improvement outcomes even for the most confident leaders. Giving managers the support they need to advocate for the developmental needs of their direct reports can have a strong impact on leadership development outcomes; however, it may also help to look into how others in a leader’s network can help champion their development.11

Just as athletes need to continue practicing following a training camp, leadership development doesn’t end when a formal program does. For organizations who want to ensure leadership development proves to be a wise investment, providing opportunities for post-program growth will have a large influence on the initiative’s outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- Leaders who have support from their organizations to apply the skills they learned in formal leadership development programs will experience greater improvement in their leadership skills.

- Even highly committed and confident leaders benefit from managerial and organizational support for their development goals.

- Organizations can bolster the results of formal leadership development by providing support for continued learning, application, and stretch assignments.

References

1McCauley, C.D., Kanaga, K., & Lafferty, K. (2010). Leadership development systems. In E. Van Velsor, C.D. McCauley & M.N. Ruderman (Eds.), Handbook of Leadership Development (pp. 29-61). Jossey-Bass.

2Sørensen, P. (2017). What research on learning transfer can teach about improving the impact of leadership-development initiatives. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000072

3Leading Effectively Staff (2020, July 6). How bosses can support their employees’ development. Center for Creative Leadership. https://www.ccl.org/articles/leading-effectively-articles/practical-ways-boss-support-development/

4Stawiski, S., Jeong, S., & Champion, H. (2020). Leadership Development Impact (LDI) Framework. Center for Creative Leadership. https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.2020.2040

5Tonidandel, S. & LeBreton, J. M. (2014). RWA-Web — A free, comprehensive, web-based, and user-friendly tool for relative weight analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10869-014-9351-z

6Gurvis, J., McCauley, C., & Swofford, M. (2016). Putting experience at the center of talent management [White Paper]. Center for Creative Leadership. https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.2018.1069

7Leading Effectively Staff (2022, April 24). The 70-20-10 rule for leadership development. Center for Creative Leadership. https://www.ccl.org/articles/leading-effectively-articles/70-20-10-rule/

8Young, S., Champion, H., Raper, M., & Braddy, P. (2017). Adding more fuel to the fire: How bosses can make or break leadership development programs and what organizations can do about it [White paper]. Center for Creative Leadership. https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.2017.1072

9Leading Effectively Staff (2022, September 1). 5 powerful ways to take REAL action on DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion). Center for Creative Leadership. https://www.ccl.org/articles/leading-effectively-articles/5-powerful-ways-to-take-real-action-on-dei-diversity-equity-inclusion/

10Reeves, M. (2021, July 5). Mentorship vs sponsorship: Why both are important. Together: Diversity and Inclusion. https://www.togetherplatform.com/blog/mentorship-sponsorship-differences

11Reinhold, D., Patterson, T., & Hegel, P. (2015). Make learning stick: Best practices to get the most out of leadership development [White paper]. Center for Creative Leadership. https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.2015.2043

[i] We used exploratory factor analysis, a statistical method that can condense information from the eight survey questions to systematically create a single score for each participant. This resulted in a standardized composite score for each participant that captured the range of responses from above average to below average levels of perceived improvement.