By: Andy Loignon and Diane Bergeron

A year ago, for one of us (Andy) the news of a large shipping vessel, the Ever Forward, running aground in the Chesapeake Bay struck close to home (literally and figuratively). For days the vessel remained wedged on the murky bottom of the bay despite various attempts to dredge and propel it free.1 It was only after nearly five weeks, through the combined efforts of several tugboats, barges, and an unusually high tide, that the ship floated free.i

What made this event more interesting, and particularly relevant to our work at the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL), is what caused the ship to run aground. While exiting the bay, the ship missed a turn toward safer passage and instead inadvertently headed towards shallow water. According to an investigation by the U.S. Coast Guard and reporting by the Washington Post, at this point “the ship’s third officer, the senior crew member on the bridge while the captain was having dinner, announced the ship’s heading and speed in an apparent effort to prompt the pilot to correct course, but didn’t directly say the turn had been missed.”ii

How Formal Positions of Leadership Affect Voice

It’s that sentence’s last clause that caught our attention – didn’t directly say the turn had been missed. This is a striking example of how employees can fail to use their voice to express concerns. Employee voice is an “informal and discretionary communication of ideas, suggestions, concerns, problems or opinions about work-related issues, with the intent to bring about improvement or change” (p. 10).iii Unfortunately, the phenomenon of employees not speaking up is far too common and emerges in other high-stakes situations. For example, 60%-80% of aviation accidents are attributed to human error; many occurring due to miscommunication between pilots and co-pilots.iv v Similarly, hospital medical errors occur due to a reluctance of some employees (e.g., nurses) to directly challenge or express concerns to higher status colleagues (e.g., doctors).vi

By looking across these examples, a theme emerges: hierarchical differences in formal leadership positions can limit the expression of employee voice. That is, in each of these examples, a person who occupied a lower-authority position (e.g., third officer, co-pilot, nurse) was disinclined to challenge the decisions of the person who occupied a higher-authority position (e.g., captain, pilot, physician).

Individuals often view speaking up to those in authority as risky – and have valid career, reputation and relational concerns about doing so.vii viii ix As such, employees assess how leaders respond to ideas, suggestions, and opinions when considering whether to use their voice.x xi xii These perceptions then inform a mental ‘safety-efficacy’ calculusxiii in which employees weigh the potential costs of whether speaking up versus not speaking up will make any difference. Taken together, this suggests that eliciting ideas and input from all employees is not simply a question of how people think, feel, or act. Instead, how a team or organization is designed (i.e., the presence or absence of a formal leader) also has significant implications for how ideas and information are distributed or shared.xiv

How Leaders Can Encourage ‘Voice’

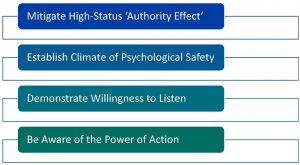

There are several ways in which leaders can encourage employee voice (see Figure 1 for an overview).

Figure 1. Four Ways Leaders Can Encourage Employee Voice

- First, leaders can mitigate the high-status ‘authority effect.’ Leaders need to recognize that their position can often be a barrier to getting necessary information from employeesxv and that they need to actively counteract their more powerful formal position. Using more relational and democratic leadership styles can help to elicit more employee voice.xvi Using inclusive language is also positively related to voice.xvii Imagine how things might have been different if the Ever Forward’s captain had begun the voyage by saying, “We might have different responsibilities and ranks, but your perspectives are important to me.” Would this have been enough of a cue for the third officer to give a more explicit warning?

- Second, leaders can establish a climate of psychological safety. Leaders need to recognize the risk employees take when they speak up. Research shows that listening is positively related to psychological safety,xvii which is a strong predictor of employee voice.xix In a sample of medical professionals working in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), employees felt greater psychological safety if the physicians within their unit asked for input from their colleagues.xx This was also associated with a greater likelihood that the NICU would engage in quality improvement processes, thus highlighting the desired outcomes of voice. Leaders can also role model speaking up and encouraging others to do the same. When others speak up, there seems to be a voice contagion That is, seeing a coworker engage in voice seems to increase the likelihood that another employee will speak up.xxi

- Third, leaders can demonstrate a willingness to listen. Most leaders overestimate their listening abilities.xxii One way that leaders can signal a willingness to listen is by making time and space for employees to speak up. This includes eliminating distractions and providing enough time to fully understand the issue or concern. It is notable that the ship’s captain was on their phone at several points throughout the Ever Forward’s voyage, which was cited as a contributing factor in the crash.xxiii Although most leaders are not tasked with navigating the high seas, it is worthwhile to consider contextual distractions. Beyond cell phones, there are many other technologies (e.g., Microsoft Teams notifications, e-mail) that can be similarly distracting and might draw a leader’s attention away from a conversation. Research shows that such distractions make employees feel that leaders are not listening.xxiv Leaders can send signals about active listening through verbal acknowledgements (e.g., asking questions, using ‘uh-huh’) and nonverbal gestures. Non-verbal cues, like head nods and eye contact, can signal that one is attentive and ready to listen.xxv Likewise, failing to provide these conversational cues can send other signals, such as reinforcing higher status.xxvi Thus, the captain being oriented towards their phone may have further dissuaded the third officer from more directly engaging about being off course.

- Finally, leaders should be aware of the power of action. Because employees speak up with the intent to bring about positive change, being responsive to employee voice is important. Unfortunately, voice is often not acted upon. A recent study of healthcare teams found that only 24% of voiced ideas were implemented.xxvii When leaders take appropriate action, employees are more likely to speak up.xxviii Taking action also allows employees to feel that leaders are listening, which subsequently makes them more likely to speak up again in the future.xxix When action is not possible, providing employees with a sensitive and specific explanation for why action is not feasible may help.xxx In addition, it may be useful to validate the idea or suggestion raised within voice (e.g., verbally express agreement) or to acknowledge that the employee spoke up with a concern or suggestion to further encourage this behavior.xxxi

Do These Dynamics Happen with Shared Leadership?

Unfortunately, the answer to this question is yes. Shared leadership occurs when leadership roles and influence are distributed among team members.xxxii In such situations, it can be tempting to conclude that these dynamics would be less likely to occur with shared leadership structuresxxxiii; however, shared leadership structures can fall victim to the same dynamics – just more subtly. That is, rather than deference to formal authority based on hierarchical rank or title, the deference is based on more informal characteristics (e.g., such as personality, agentic behaviors, gender, ethnicity or social class).xxxiv xxxv xxxvi This again creates the risk that certain individuals within the team may withhold their contributions and be less willing to challenge the ideas put forward by their more influential and outspoken colleagues.

Final Thoughts

We acknowledge that the grounding of the Ever Forward, with an estimated $100 million cost to be freed, is an extreme example of the price of failing to listen.xxxvii Nevertheless, it provides a useful example. There are many benefits to formal leadership positions, including explicit and faster decision-making processes. In some contexts (e.g., transportation, military, or medical settings), such benefits may be critical for a team or organization’s success.xxxviii By highlighting the ways that formal leaders can either elicit or limit employee voice, we hope we can help other leaders and organizations prevent similar events from unfolding and instead capture the innovation, creativity and improved decision making that can result from voice.xxxix

[1] This incident could easily be confused with the grounding of the Ever Given in the Suez Canal, which blocked a major shipping channel and cost various stakeholders millions of dollars. In fact, both ships are owned and operated by the same parent company. From an organizational perspective, the two incidents may represent an unintended consequence of such firms increasing reliance on larger vessels, despite the associated risks, in order to leverage economies of scale. However, the downsides of “doing more with less” is a topic best left for a separate blog post.

References

i Diaz, J. (2022). The Ever Forward is finally free from the Chesapeake Bay — one month later. https://www.npr.org/2022/04/17/1093245643/ever-forward-freed-maryland

ii Duncan, I. (2022). Chesapeake Bay ship pilot was on phone before Ever Forward ran aground. https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2022/12/07/ever-forward-chesapeake-bay-investigation/

iii Morrison, E. W. (2023). Employee voice and silence: Taking stock a decade later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 79-107.

iv Jentsch, F., Barnett, J., Bowers, C. A., & Salas, E. (1999). Who Is Flying this plane anyway? What mishaps tell us about crew member role assignment and air crew situation awareness. Human Factors, 41(1), 1-14.

v Salas, E., Burke, C. S., Bowers, C. A., & Wilson, K. A. (2001). Team training in the skies: does crew resource management (CRM) training work? Human Factors, 43(4), 641-674.

vi Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 941-966.

vii Ashford, S. J., Rothbard, N. P., Piderit, S. K., & Dutton, J. E. (1998). Out on a limb: The role of context and impression management in selling gender-equity issues. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(23-57).

viii Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869-884.

ix Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706-725.

x Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869-884.

xi Dutton, J. E., Ashford, S. J., O’Neill, R. M., Hayes, E., & Wierba, E. E. (1997). Reading the wind: How middle managers assess the context for selling issues to top managers. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 407-423.

xii Edmondson, A. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419-1452.

xiii Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373-412.

xiv Lee, S. M., Koopman, J., Hollenbeck, J. R., Wang, L. C., & Lanaj, K. (2015). The Team Descriptive Index (TDI): A multidimensional scaling approach for team description. Academy of Management Discoveries, 1(1), 5-30.

xv Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 173-197.

xvi Morrison, E. W. (2023). Employee voice and silence: Taking stock a decade later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 79-107.

xvii Weiss, M. L., Kolbe, M., Grote, G., Spahn, D. R., & Grande, B. (2018). We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams. The Leadership Quarterly, 29, 389-402.

xviii Lin, X., Chen, Z. X., Tse, H. H. M., Wei, W., & Ma, C. (2019). Why and when employees like to speak up more under humble leaders? The roles of personal sense of power and power distance. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 937-950.

xix Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869-884.

xx Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 941-966.

xxi Ng, T. W. H., Lucianetti, L., Hsu, D. Y., Yim, F. H., & Sorensen, K. L. (2021). You speak, I speak: The social‐cognitive mechanisms of voice contagion. Journal of Management Studies, 58(6), 1569-1608.

xxii Brownell, J. (1990). Perceptions of effective listeners: A management study. Journal of Business Communication, 27, 401-415.

xxiii Duncan, I. (2022). Chesapeake Bay ship pilot was on phone before Ever Forward ran aground. https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2022/12/07/ever-forward-chesapeake-bay-investigation/

xxiv Bergeron, D. M., Rochford, K., & Cooper, M. C. (2023). Actions speak louder than (listening to) words: The role of leader action in encouraging employee voice. Center for Creative Leadership.

xxv Cooney, G., Mastroianni, A. M., Abi-Esber, N., & Wood Brooks, A. (2020). The many minds problem: Disclosure in dyadic versus group conversation. Current Opinions in Psychology, 31, 22-27.

xxvi Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2009). Signs of socioeconomic status: A thin-slicing approach. Psychological Science, 20, 99-106.

xxvii Satterstrom, P., Kerrissey, M., & DiBenigno, J. (2021). The voice cultivation process: How team members can help upward voice live on to implementation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 66, 380-425.

xxviii Janssen, O., & Gao, L. (2015). Supervisory responsiveness and employee self-perceived status and voice behavior. Journal of Management, 41(7), 1854-1872.

xxix Bergeron, D. M., Rochford, K., & Cooper, M. C. (2023). Actions speak louder than (listening to) words: The role of leader action in encouraging employee voice. Center for Creative Leadership.

xxx King, D. D., Ryan, A. M., & Van Dyne, L. (2019). Voice resilience: Fostering future voice after non-endorsement of suggestions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92, 535-565.

xxxi Bergeron, D. M., Rochford, K., & Cooper, M. C. (2023). Actions speak louder than (listening to) words: The role of leader action in encouraging employee voice. Center for Creative Leadership.

xxxii Zhu, J., Liao, Z., Yam, K. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Shared leadership: A state-of-the-art review and future research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(834-852).

xxxiii Zhu, J., Liao, Z., Yam, K. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Shared leadership: A state-of-the-art review and future research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(834-852).

xxxiv Anderson, C., & Kilduff, G. J. (2009). Why do dominant personalities attain influence in face-to-face groups? The competence-signaling effects of trait dominance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(2), 491-503.

xxxv Loignon, A. C., & Kodydek, G. (2022). The effects of objective and subjective social class on leadership emergence. Journal of Management Studies, 59(5), 1162-1197.

xxxvi Paunova, M. (2015). The emergence of individual and collective leadership in task groups: A matter of achievement and ascription. The Leadership Quarterly, 26, 935-957.

xxxvii Shwe, E. (2022). Financial Cost and Environmental Impact of Ship Freed from Chesapeake Bay Muck Remain Uncertain. https://www.marylandmatters.org/2022/04/18/financial-cost-and-environmental-impact-of-ship-stuck-in-chesapeake-bay-remain-uncertain/

xxxviii Lee, S. M., Koopman, J., Hollenbeck, J. R., Wang, L. C., & Lanaj, K. (2015). The Team Descriptive Index (TDI): A multidimensional scaling approach for team description. Academy of Management Discoveries, 1(1), 5-30.

xxxix Bashshur, M. R., & Oc, B. (2015). When voice matters: A multilevel review of the impact of voice in organizations. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1530-1554.