By: Judanne Lennox-Morrison, Michelle Schneider and Valerie Ehrlich

This post features evaluation research by our 2022-2023 American Evaluation Association Graduate Education Diversity Internship (GEDI) scholar, Judanne Lennox-Morrison. This program pairs emerging evaluators with organizations to build shared learning and competencies around program evaluation and culturally responsive research methods.

Researcher as Instrument

Validity in research is not always synonymous with objectivity. As a Graduate Education Diversity Internship (GEDI) Scholar, I learned to delve deeper, focusing on untold stories and unheard voices. I was taught to interrogate that even more by focusing on participant voice and the stories not readily told. The GEDI program, developed by the American Evaluation Association, aims to engage students from underrepresented groups in the field of evaluation. My placement was at the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL) in the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion practice, a group dedicated to fostering a more inclusive and diverse global leadership environment.

My goal was to gain critical tools and ways of addressing equity challenges and disparate vulnerabilities in underserved communities, particularly in disaster and hazard research. As a scholar-activist with over seven years of professional experience in emergency management, community engagement, and urban planning. I bring a unique perspective and framing when addressing “wicked problems.” My approach to addressing “wicked problems” – complex, pervasive issues immune to conventional solutions – is informed by my background in social justice and feminist participatory methods.

Parallels of Disaster Management & Program Evaluation

Both disaster research and program evaluation have tried to address many of society’s wicked problems such as poverty, racism, low socio-economic opportunities, and the intersection of these challenges in different communities. In disaster research, it is well documented that underserved communities and communities of color suffer disproportionate impact from disasters due to environmental racism and historic disenfranchisementi ii. Both fields of disaster research and program evaluation have experienced troubled histories with issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI). A lack of diverse representation often results in a limited understanding of communities of color. This is worsened by a transactional extractive view of research and a view of community members as “subjects.” However, there has been a shift towards centering equity and ethical challenges using participatory action researchiii. I use my participatory praxis, lived experiences and drive to challenge equity issues, as a lens to explore the effectiveness and impact of EDI programs. These experiences shape how I generate and interpret data making me a more effective and culturally competent hazard and disaster researcher. In qualitative research, where stories and narratives are woven through the data, the researcher is the primary instrument for data collection and interpretation.

Subverting Traditional Program Evaluation

This blog investigates several key questions:

- How can a deeper understanding of participant experiences in Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) programs influence CCL’s approach to preparing new facilitators?

- What can CCL learn from this process to inform the current leadership and EDI-specific leadership program evaluation design?

- How can my experiences as a GEDI Scholar contribute to answering these questions?

Scrutinizing EDI program design frameworks is crucial, especially given the rising critique of EDI programs’ effectiveness. For instance, a CCL study found that most EDI statements were superficial, lacking detailed accountability strategies and plans for organizational cultural shiftsiv. These hollow corporate approaches often lead to deserved skepticism towards EDI programs that fail to challenge systemic oppression. After delivering numerous EDI programs using diverse methods, we aimed to understand the effective elements and areas for improvement. We acknowledged criticisms that EDI training programs seldom bring about structural change and lack rigorous evaluationv. We questioned whether our traditional evaluation methods might be reinforcing our reliance on satisfaction metrics.

To create meaningful experiences that can instigate genuine EDI change, we need to empower participants to have an equal voice alongside program evaluation stakeholders. We concluded that traditional evaluation methods might not be adequate for the continuous improvement of EDI solutions, nor should they be. Traditional evaluation methods, like disaster research, aim to support decision-making on inherently political and complex issues. However, these methods often overlook participants, overemphasize outcomes, and struggle to challenge existinginequitiesvi. In EDI programs, addressing issues requires confronting systems of oppression, privilege, and power imbalances. By sticking to traditional evaluation methods, we risk assessing impact and EDI issues from a deficit perspective.

Adopting an Emergent and Equitable Evaluation Approach

At CCL, evaluating leadership development programs is important for the organization as it allows for continuous improvementvii. After every engagement, participants are asked to complete an evaluation that includes two open-ended questions: “What was most helpful?” and “What changes would you recommend for improvement?” Similarly, after CCL faculty undergo EDI-specific training, they are asked to complete an evaluation, including the question “What would help you feel more prepared to deliver EDI programs?”

For this project, it would have been sufficient to analyze participant data only and focus specifically on quantitative metrics. However, we adopted an emergent evaluation approach, exploring a possible link between faculty preparation evaluation data and participant program evaluation data from EDI-specific programs. Instead of focusing on quantitative metrics, such as mean scores, we prioritized qualitative data – the experiences and words of our participants and faculty.

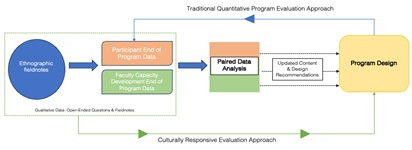

We examined responses to the open-ended questions from both participants and faculty. This approach subverts the traditional program design and evaluation process, begins with the participant, and asks about their experience. Their experiences are paired with a narrative of the concerns and curiosities of faculty developing to facilitate EDI specific content.

Figure 1- Taking a Culturally Responsive & Equitable Approach to Evaluation

We analyzed participant experience in EDI programs and faculty perceptions related to their readiness for program delivery to understand how we might create the most meaningful EDI capability development for faculty, and program experience for participants. As an intern who

We analyzed participant experience in EDI programs and faculty perceptions related to their readiness for program delivery to understand how we might create the most meaningful EDI capability development for faculty, and program experience for participants. As an intern who

participated in two CCL leadership development programs, I used ethnographic methods and participation observation to collect primary data on current EDI programs. Then using content analysis and thematic mapping, we analyzed over 2,700 open-ended responses from approximately 2,506 participants and 293 faculty feedback responses, from evaluations of EDI programs over a two-year period.

We found that participant and facilitator experiences were often related. Both perspectives were in dialogue with each other, as we found on several occasions, that competencies successfully learned in faculty preparation could be mapped to a positive experience in EDI programs. By pairing faculty training feedback with end-of-program participant feedback, we found that faculty preparation could improve the impact of EDI programs. This feedback can provide the input for continuous improvement of EDI programs, unlike traditional evaluation methods, which often regard it as standalone output.

Evaluation Findings: Reimagining EDI using a CREE Framework

Culturally responsive equitable evaluation (CREE) offered a conceptual framework for our insights. CREE asks us to consider ‘In whose name are we doing this work?” in the words of Dr. Hazel Symonetteviii. My questions and grounding rests on the persistent and reflective question: “Whose story is not being elevated and how can I do that?” When I apply the reflexive frame to leadership development evaluation (or disaster management, or urban planning, or public health), it brings the experience of participants (or community members) into focus. This is especially crucial in EDI programs where participant experiences can be transformative or potentially harmful, and facilitator preparation is key.

Insights for CCL Programs

Our analysis revealed key insights for program design, content development, and implementation for faculty and participants.

- Self-directed learning opportunities, reflection time, and rest periods are essential for effective learning.

- Diverse perspectives are critical in EDI programs and more opportunities for interaction and peer-to-peer sharing can foster those experiences.

- Incorporating reflective journaling sessions can increase the likelihood of absorbing training content.

- The integration of existing research, tools, and frameworks developed by CCL’s EDI Practice into training content and programs will strengthen content.

- Real-life scenarios can help participants apply existing tools like action plans, leadership frameworks, and checklists.

- Inclusivity should be promoted by adopting accessibility standards and incorporating closed captioning.

- A balance is critical between timekeeping and addressing participants’ needs and questions to create a space of vulnerability, safety, and authenticity.

- Pre-assessment tools should be developed to tailor EDI programs more effectively to participants’ goals and get the most from peer-to-peer interactions.

- The competencies of new faculty can be sharpened by implementing a community of practice that includes coaching, mentorship, and skills practice.

- Client and participant expectations about the importance of EDI in leadership development need to be addressed effectively.

Conclusion and Reflections

This approach prioritized the voices of participants (both faculty and program participants), providing a more comprehensive analysis of program success/impact. A traditional approach would have started with satisfaction scores and learning objectives, aiming to understand which design elements worked and which did not. While there is value in that type of evaluation, for EDI work, it begs the question of what we might lose when we refuse to expand our view of program evaluation beyond our obsession with metrics? Furthermore, how might our success measures for program evaluation and disaster management be redefined if we adopted culturally responsive and humanist methods? What questions would we ask of our programs if we first sought to understand the participant experience, then considered the interaction between faculty and participant and how they co-create that experience?

Reflecting on my academic year internship with CCL, I realize a more transactional approach would have resulted in a presentation outlining which program elements drove outcomes. However, it might not have so clearly highlighted the human-centered aspect of faculty capability development that is crucial for delivering effective, adaptable EDI programs in our ever-changing societal and business landscape. All of which would not have been realized without my lived experiences and work as a culturally responsive evaluator and disaster researcher.

i Méndez, M., Flores-Haro, G., & Zucker, L. (2020). The (in)visible victims of disaster: Understanding the vulnerability of undocumented Latino/a and indigenous immigrants. Geoforum, 116, 50–62 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.07.007

ii Bolin, B., & Kurtz, L. C. (2018). Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Disaster Vulnerability. In H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, & J. E. Trainor (Eds.), Handbook of Disaster Research (pp. 181–203). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_10

iii Schneider, M. & Hamill, J. Practicing what we teach: Early lessons in listening to and learning from participants leads to program effectiveness. Center for Creative Leadership.

iv Dawkins, M. & Balakrishnan, R. Cosmetic, Conversation, or Commitment: A Study of EDI Corporate Messages, Motives, and Metrics After George Floyd’s Murder. https://cclinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/cosmetic-conversation-or-commitment.pdf

v Singal, J. (January 23, 2023). What if Diversity Trainings are Doing More Harm than Good. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/17/opinion/dei-trainings-effective.html

vi Worthen, B. R., Sanders, J. R., & Fitzpatrick, J. L. (1997). Program evaluation. Alternative approaches and practical guidelines, 2, 42-47.

vii Stawiski, S., Jeong, S., & Champion, H. Leadership Development Impact (LDI) Framework. https://cclinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/evaluationframeworkldi.pdf

viii Symonette, H. (2009). Cultivating self as responsive instrument. Handbook of social research ethics, 279-294.

-

Judanne Lennox Morrison Evaluation Analyst

Judanne Lennox Morrison Evaluation Analyst -