Each spring, the top 16 of the 32 teams from the National Hockey League (NHL) vie for one of the most celebrated trophies in professional sports – The Stanley Cup. Teams who win “The Cup” get their names engraved along with past winners and each player gets to spend one day with the trophy. Hockey is a physically demanding sport. It requires honed skills, combined with endurance, strength and mental toughness, in every game for 82 games, and that’s just to make the playoffs. To win the Stanley Cup, teams must win 16 more times, potentially playing up to 28 additional games (i.e., four rounds, best of seven games).

Each spring, the top 16 of the 32 teams from the National Hockey League (NHL) vie for one of the most celebrated trophies in professional sports – The Stanley Cup. Teams who win “The Cup” get their names engraved along with past winners and each player gets to spend one day with the trophy. Hockey is a physically demanding sport. It requires honed skills, combined with endurance, strength and mental toughness, in every game for 82 games, and that’s just to make the playoffs. To win the Stanley Cup, teams must win 16 more times, potentially playing up to 28 additional games (i.e., four rounds, best of seven games).

Team leaders outside hockey can empathize with such a daunting challenge. In the past few years, global leaders working in various industries have led their teams through a global pandemic, work shutdowns and stoppages, heightened economic volatility, and increasingly disruptive technological advancements. Here, we couple Martin’s experience as a hockey player and professional skating coach with Andy and David’s enthusiasm for research and data to highlight three lessons that today’s leaders can glean from NHL teams.

Lesson 1: Great Teams Aren’t Simply Built – They Are Developed

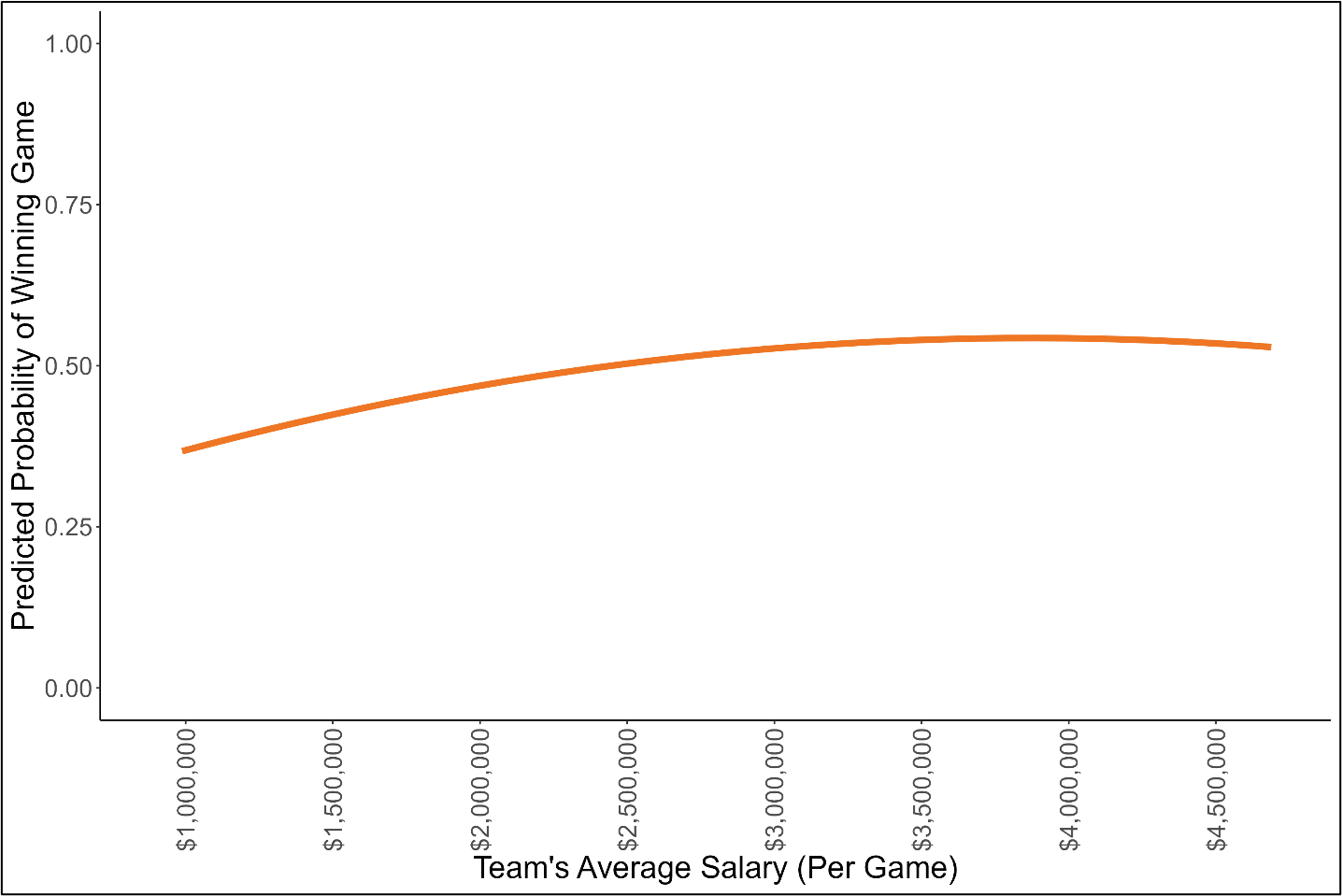

A key decision for most leaders is selecting the members of their team. And, certainly, how a team is built matters.i Our findings using NHL data from 32 teams across several seasons suggest that composing a team is only the beginning when it comes to developing effective teams. In fact, we found that the average amount of money teams spend on player salaries per game is a weak predictor of the team’s likelihood of success.ii Furthermore, teams who spend the most are no more or less likely to win than teams who spend an average amount on their players.

Figure 1. There are Diminishing Returns when Investing in NHL Talent

This figure illustrates the diminishing effects for higher salaries on a team’s likelihood of winning a game. A team could nearly double its salary spent on players and only expect to see a 3% absolute increase in winning percentage. For example, if a team spends $2,500,000 per game on their players (an average amount in the NHL), the predicted likelihood of their winning a game is 51%. A team that spends $4,500,000 per can expect a win percentage of 54%. These types of diminishing returns are not unique to hockey. The effect is so robust it’s sometimes referred to as the “too much talent effect” and can be found in other sports.iii Moreover, this effect has been replicated in financial and medical organizations.iv

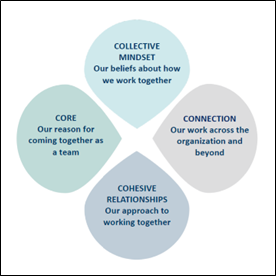

These findings and experiences point to several lessons for leaders. First, team dynamics are just as important as building a team. Once your people are in place, this is often only the beginning of your team’s developmental journey toward success. Within CCL’s Team Effectiveness Framework (Figure 2), an emphasis Core is one aspect of effective teamwork and reflects the team’s purpose, practices, and people. Thus, composing a team is only one component of the model. The remaining components (i.e., Collective Mindset, Cohesive Relationships, and Connection) represent other ways that teams can become more effective, independent of the talent within the group.

Figure 2. CCL’s Team Effectiveness Framework

The diminishing returns on salaries in hockey teams also point to lessons for leaders with limited budgets. Looking at the left-hand side of Figure 1, we see that teams with the lowest salaries (<$1,000,000 per team per game) are expected to win, on average, 36% of the time. That’s a 14% decline below the typical NHL team (i.e., a 50-50 chance to win each game). This suggests that these teams cannot compete based solely on (limited) investments in player salaries. When faced with smaller budgets, these teams must instead shift their focus from spending to finding ways to develop world-class teamwork. Thus, the critical task for leaders is finding the right mixture of acquiring and developing their available talent as a collective through an emphasis on teamwork. Just as hockey teams must respond to injuries and trades, leaders must continuously evaluate, adjust, and develop the talent in their team. Building effective teams is not as easy as simply hiring “top talent” and getting out of their way as they lead themselves and others to success.

Lesson 2: Effective Teams Consider Both the Bottomline and Their Team Processes

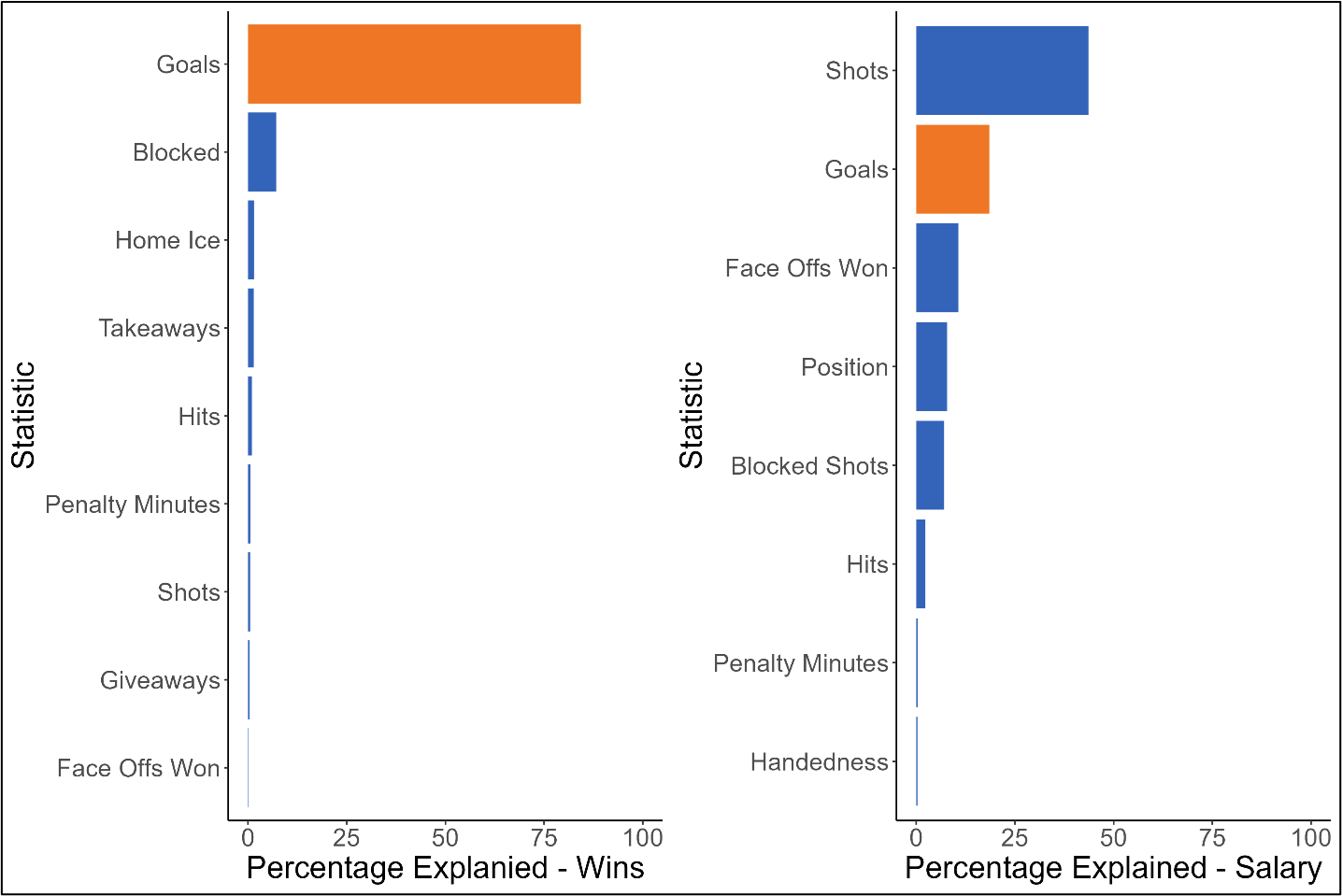

Like today’s global leaders, hockey teams are often evaluated based on their bottom-line success (i.e., wins and losses) and are in constant pursuit of finding ways to increase their performance. Our findings suggest that the likelihood of a team winning a game is almost entirely determined by the number of goals they score (see left-hand side of Figure 2).v This seemingly trite finding echoes a hockey cliché, “When you put the puck on the net, good things happen”.vi

Yet, when we examine what predicts NHL players’ compensation (cf. right-hand side of Figure 2), players are rewarded not only based on the number of goals they score (ranked 3rd in this analysis), but a range of other statistics that predict players’ salaries (e.g., shots, stopped goals, takeaways/giveaways, faceoffs, a player’s role or position, blocked shots). NHL players are rewarded for both their direct contributions to the team’s success (i.e., goals, and therefore, wins) and other efforts that contribute to these successes (i.e., faceoffs, blocked shots). Thus, these teams recognize that behind each goal scored are small and large behaviors by many members of the team working interdependently in support of the ultimate variable predicting success: goals scored. Returning to that cliché, hockey teams apparently ask themselves, “How can we put the puck on the net?” versus “Get out on the ice and put the puck in the net.”

Figure 3. Even though Goals are Paramount, NHL Players are Paid based on a Range Activities

It is understandable that leaders focus on the most observable and seemingly important metrics.vii This bottom-line mentality, though, overlooks the processes that need to be in place to achieve the desired results. This is especially true, and perhaps even more difficult, in teams. Leaders must focus attention on fundamental team processes like back-up and support and coordinatingviii and a team’s climate to achieve success.ix Likewise, Diane Bergeron, our colleague at CCL, discusses the need to recognize and reward the “citizenship” behaviors that allow an organization to operate, but often fall between the cracks of formal job descriptions.x Still, investing time to identify, recognize, and cultivate such behaviors is key to helping a team develop.

Similarly, these data highlight a need to think broadly about the types of roles team members perform, how those roles fit together, and how to manage such roles over time. Take, for example, a sales team. It might be tempting to create a group that consists entirely of “closers” who each are adept at convincing prospective clients to purchase the company’s products or services. However, this would be akin to a hockey team that consists entirely of goal scorers. Based on our data, such an approach is likely to bode poorly for a team’s performance. In fact, prior research has found that losing a hockey team’s enforcer (i.e., the player who is most likely to engage in fights with other teams) can be just as detrimental as losing a star scorer or the team’s goalie.xi In organizations, a leader might ask themselves: Who’s volunteering for less glamorous tasks? Who’s helping others even if they’re busy? Who’s making connections beyond our team? Such questions might help steer one away from an emphasis on stars and better appreciate the entire team. The data are clear: all players matter. Great teams leverage the skills of every team member.

Lesson 3: (Even Effective) Teams Experience Ups and Downs

A good coach is a critical factor in the team’s success. They build a winning culture, develop a system based on the strengths of all the players (not just the stars), and make adjustments throughout the season and during games as needed. They motivate the players and remove the distractions that gets in the way of them playing their best.

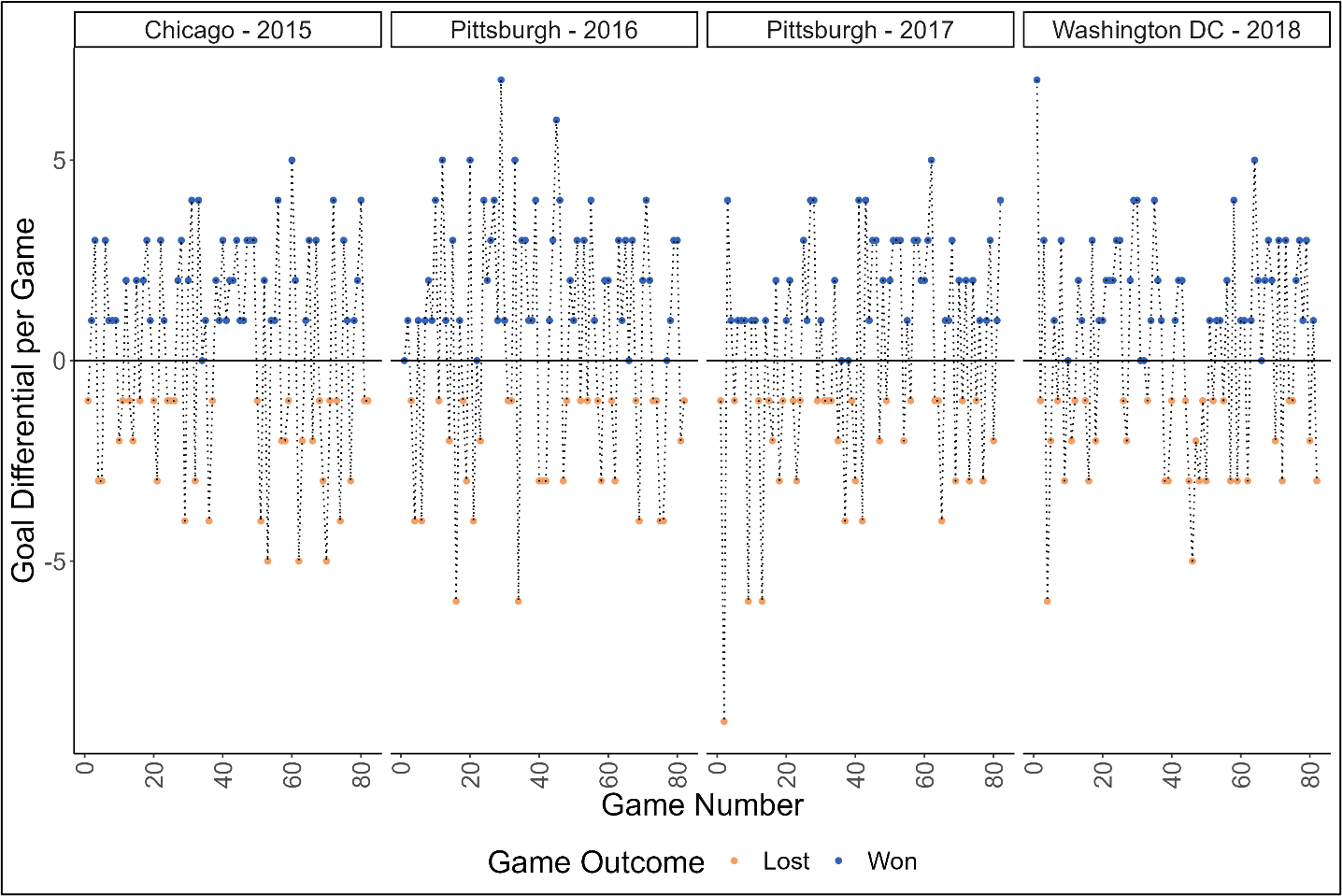

Given the pace at which today’s leaders must operate, it can be difficult to reflect on where their team is going and where it has been. However, such a perspective can be illuminative. Consider the four timeseries plots below in Figure 4: one for each NHL team for the 2015-2018 seasons. The Y-axis going up the left-hand side of the figure represents the team’s goal differential each game (i.e., how much they outscored, or were outscored by, their opponent) and the dots are color coded for wins and losses. Each line depicts a team’s “winning” trend over the course the 82-game season.

Three findings stand out in these data. First, there is no clear upward or downward trend – teams do not perform increasingly better or worse over the 82-games.xii Second, there can be big swings in a team’s level of performance. Take the Washington Capitals in 2018 (far right-hand side of Figure 4). They began their season by beating an opponent by more than 7 goals, but just a few days later lost by nearly as many goals. Third, such variability is not, at least inherently, a sign of a poor performing team. Each one of the teams depicted in Figure 4 eventually won the Stanley Cup that year. In fact, we observe similar patterns, albeit in the opposite direction (i.e., more losses than wins), for teams that were the lowest performers each of these four seasons (we won’t name names!).

Figure 4. Hockey Teams Experience Ups and Downs (Even on the Way to Championships)

These findings and experiences point to ways that leaders can help their team develop and become more resilient. First, this finding demonstrates how dynamic teams can be.xiii Whether a team is experiencing changes brought about by new business needs or emerging technologies, or if it has lost group members and had to onboard replacements, it is quite likely that the team we are a part of today will be very different from the team we are working with in the future. This means that when it comes to team development, leaders can’t simply “set it and forget it,” but should regularly re-engage their team members in efforts to improve key aspects of their effectiveness (cf., Figure 2).

Second, leaders might benefit from adopting a relevant hockey adage: “We’re Going to Take Them One Game at a Time.” This reflects a need to prepare for each opponent, recover after each game, constantly build a team climate that adapts to changing conditions, and move on to the next challenge with new individual and team mindsets and skills. In fact, we found some evidence of that NHL teams experience cycles performance cycles approximately every 8 games where they would outscore another team by several goals, have several close matches, and then lose a game by several goals. This suggests that leaders may have to manage the “rhythm” of their team’s performance over time.

Conclusion

At first glance, it may not be evident that hockey has insights to offer today’s leaders. After all, very few of us find ourselves skating at high speeds, barreling into others, and wielding a stick all in pursuit of a small puck, which we then try to get past a heavily padded player into a small net. Yet, if we consider the fundamental features of hockey teams (i.e., a collective of players in pursuit of a shared objective), and bring together data and firsthand experience to bear, several lessons emerge. Notably, it would behoove leaders to (1) invest as much, if not more, in their teams development as they do in composing their team, (2) intentionally recognize the effort and behavior that gives way to their team’s achievements, and (3) manage the regular ups-and-downs that come with being a team and use those ups-and-downs as fuel for improved performance.

The data and lessons from hockey are clearly relevant to leaders in other settings, industries, and sectors. Today’s leaders must be able to synthesize more input from more diverse source at a much faster pace than ever before. Hockey coaches and business leaders have a lot in common. They both need to attract and develop the right talent, motivate, and inspire the team, and set the culture that gives the organization the highest probability of success. Such lessons should help your team make it through your ongoing “playoffs” and find your team celebrating like past and future NHL champions.

References

i Wolfson, M. A., D’Innocenzo, L., & Bell, S. T. (2022). Dynamic team composition: A theoretical framework exploring potential and kinetic dynamism in team capabilities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(11), 1889.

ii These findings are based on a generalized estimation equation that incorporates fixed effects for season and team and nests observations from all 32 teams within games (8,799 observations). Data pertain to the 2012-2018 seasons. The model also controls for the home or away status of teams.

iii Swaab, R. I., Schaerer, M., Ancich, E. M., Ronay, R., & Galinsky, A. D. (2014). The too-much-talent effect: team interdependence determines when more talent is too much or not enough. Psychological Science, 25(8), 1581-1591.

iv Call, M. L., Campbell, E. M., Dunford, B. B., Boswell, W. R., & Boss, R. W. (2020). Shining with the stars? Unearthing how group star proportion shapes non-star performance. Personnel Psychology, 74(3), 543-572

v These findings pertain to the 2012-2018 seasons and are based on17,000 team-game observations when predicting wins and 8,900 player observations when predicting salaries. In both models, we used fixed-effects models that control for season- and team-level effects. The focal statistics are derived using dominance analysis (Braun, Converse, & Oswald, 2019). For the sake of parsimony, this analysis excludes goalkeepers whose performance is tracked with an entirely different set of metrics.

vi Kurtzberg, B. (2012). NHL: 20 Most Overused Cliches in Hockey. Retrieved from https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1308049-nhl-20-most-overused-cliches-in-hockey

vii Kerr, S. (1995). On the folly of rewarding A while hoping for B. Academy of Management Executive, 9(1), 7-14.

viii Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E., & Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Academy of Management Review, 26(3), 356-376.

ix Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350-383.

x Bergeron, D., & Rochford, K. (2022). Good Soldiers versus Organizational Wives: Does Anyone (Besides Us) Care that Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scales Are Gendered and Mostly Measure Men’s—but Not Women’s—Citizenship Behavior? Group & Organization Management, 47(5), 936-951.

xi Stuart, H. C., & Moore, C. (2017). Shady characters: The implications of illicit organizaitonal roles for resilient team performance. Academy of Management Journal, 60(5), 1963-1985.

xii In fact, when we estimated a series of dynamic structural equation models, we found minimal support for a linear trend in team performance across games. Instead, we observed negative and consistent autoregressive effects (AR2). This suggests that if teams performed exceptionally well (poorly) in an earlier game, the most likely outcome in their subsequent game was for them to perform worse (better). For more information on these models, please see: Zhou, L., Wang, M., & Zhang, Z. (2021). Intensive longitudinal data analyses with dynamic structural equation modeling. Organizational Research Methods, 24(2), 219-250.

xiii Loignon, A. C., Wormington, S., & Hallenbeck, G. S. (2022). Reconsidering Myths and Misperceptions about Teamwork Using CCL’s Framework on Team Effectiveness (C. f. C. Leadership Ed.). Greensboro, NC.