By Jeff Kosovich, Valerie Ehrlich, & Stephanie Wormington

Everyone at The Center for Creative Leadership (CCL)® is committed to supporting leaders from all industries, leader levels, and countries in fulfilling their potential. Part of that fulfillment takes place in experiences that support leaders on their journey to becoming a more effective leader. We know that the experiences we provide are effective, with some past participants even labeling their CCL experiences as life-changing. Despite the near-complete shift to digital delivery in the midst of COVID, initial evaluations showed that our participants are still highly satisfied with the experiences we provide. Given the many challenges of online delivery, we wanted to know more about what was keeping the “CCL magic” alive.

At the end of most sessions, participants fill out an End of Program survey (EOP) about their experiences. To get a good picture, we ask about everything from logistics and facilitators to applicability and general satisfaction. Satisfaction is used as a global metric of whether or not an experience landed, and–in this case–is our proxy for whether leaders experienced the “CCL magic” from the comfort of their home offices. We used these satisfaction ratings as a starting point for understanding if (and how) our online experiences were effective.

More than just knowing whether participants were leaving their courses satisfied, we also wanted to understand why. If an experience feels like a waste of time, fails to meet expectations, or feels too removed from their everyday lives, satisfaction ratings might suffer. We were tasked with understanding how much these factors might contribute.

To answer this question, we looked to EOP surveys from approximately 500 participants over the last several months. The overall satisfaction scores were high (4.4 on a scale of 5, 91% highly satisfied). To understand what about their experience impacted satisfaction ratings, we considered the following additional ratings as factors:

- Extent to which the content was applicable to their job or organization

- Extent to which the content was applicable to self or daily life

- Ease of their experience with the course technology

- Ease of overall course navigation

- Extent to which they felt they made meaningful connections

- Extent to which learning objectives were achieved

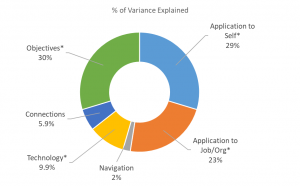

One metric for understanding how strongly a group of factors and an outcome are related is a percentage of variance explained. In this case, the variance explained tells us how much of the satisfaction scores we can account for. The fact that our variance explained was about 50% gives us confidence that we’re asking critical questions about what contributes to the leadership development experience and leaves space for us to identify other important factors.

For now, let’s look at what we can account for: how strongly does each individual factor contribute to our variance explained?

The three most important factors, by a wide margin, were:

- Application to Self/Daily Life (29.7%*)

- Learning Objectives were Achieved (29.7%*)

- Application to Job/Organization (22.8%*)

Note: these percentages are out of the 50% of variance we explained through our measurement. They were calculated using Relative Importance Analysis1. Statistically significant factors are indicated by a *.

Said another way, participants were likely to leave their experiences satisfied if they could apply what they learned to daily life and work, and felt like they learned what the experience was designed to cover.

So What?

Finding factors that were related to satisfaction was more than just luck. They were carefully selected based on decades of experience of educators and nearly a century of research on human learning and motivation across academic disciplines.

Here’s what we know about motivation and learning:

- if someone thinks that an activity is useful, important, and/or interesting, they’re more likely to engage in the activity 2,3

- people’s perceptions of a situation can affect engagement, behavior, and performance 4,5

- Motivation isn’t stagnant. Instead, it can be positively influenced by high-quality instructors, course design, and teaching practices

Data from EOP surveys confirms this and suggests that perceptions of applicability and objectives are directly related to satisfaction. As we collect longitudinal data, we’ll be able to explore how these satisfaction scores may be predictive of later leader behavior or even job performance (stay tuned!).

Now What?

EOPs don’t only include participants’ ratings of the course, but also open-ended feedback about the facilitator and overall experience. To delve even further into satisfaction, our team read and coded over 700 open-ended comments from participants. Among those with the highest satisfaction ratings, applicability of content was again noted as a key contributor to the course’s success. Amongst those who had lower satisfaction ratings, the most commonly cited area for improvement was insufficient applicability of their experience’s content. For both groups, applicability seems to be a critical factor to consider for course delivery and design.

Participants didn’t only want to see content that was applicable to their job, role, or life. They also wanted that content to be highly tangible and immediately applicable. It appears that in a highly uncertain and unpredictable world, urgency of applicability may play an even larger role in learning experiences. Time and resources are extremely limited. If participants do not leave a session with immediate applicability, it may feel like a waste of time. Skilled facilitators are key to drawing these lines of connection and sharing their experiences. We will continue to examine this trend as we hear from more participants, and as the world continues to adapt to COVID-19.

Quality Matters

Despite a global pandemic, CCL participants continue to provide high ratings of content applicability and satisfaction. While our secret sauce is a blend of many high-quality ingredients, our facilitators give it an extra kick with content applicability. We know from educational research that:

- Fostering interest leads to long-term engagement with content 6

- Extrinsic value is less motivating than intrinsic value, and less strongly related to outcomes like well-being and job satisfaction 7

- Importance for a greater purpose is particularly motivating 8

- Self-driven perceptions of importance are stronger than those imposed by others 9

Our facilitators and designers are the key ingredient to achieving these core aspects of motivation, satisfaction, and learning. Across the same experiences we analyzed, participants gave high ratings to the extent to which the facilitators provided a meaningful learning experience (4.6 on a scale of 1-5, 93% highly rated). Over 25% of our open-ended comments specifically called out facilitator actions. Through the eyes of our participants, some of the key things they experienced that supported their learning and engagement included:

- Appreciation of willingness to share personal stories and personal insights

- Providing clarity around both course content (clearly defining concepts) and course structure (establishing clear time limits and keeping discussions moving)

- Ability to push the conversation beyond the ‘comfort zone’

- Clearly connecting concepts to their job/organization/setting

- Energetic, enthusiastic, and engaging presentation style

Moving Forward

As we continue to collect data, and as face-to-face experiences eventually resume, we will further explore the unique opportunities within the virtual space. It is critical to know which delivery methods can tap into concepts of human motivation to make an experience a highly satisfying one. We will also look to our facilitators and course designers to learn more about how they put the “CCL magic” into action and help bring applicability of course material to life.

References

1 Tonidandel, S. & LeBreton, J. M. (2014). RWA-Web — A free, comprehensive, web-based, and user-friendly tool for relative weight analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s10869-014-9351-z

2 Hulleman, C. S., & Barron, K. E. (2015). Motivation Interventions in Education: Bridging Theory, Research, and Practice. In L. Corno & E. M. Anderman (Eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology (pp. 160–171). Routledge.

3 Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81.

4 Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Patall, E. A., & Pekrun, R. (2016). Adaptive motivation and emotion in education: Research and principles for instructional design. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3, 228-236.

5 Weiner, B. (1990). History of motivational research in education. Journal of educational Psychology, 82(4), 616-622.

6 Renninger, K. A., Ren, Y., & Kern, H. M. (2018). Motivation, Engagement, and Interest. In F. Fischer, C. E. Hmelo-Silver, S.R. Goldman, & P Reimann. International handbook of the learning sciences, (pp. 116–127). Routledge.

7 Kreiger, L. S., & Sheldon, K. M. (2015). What makes lawyers happy? A data-driven prescription to redefine professional success. George Washington Law Review, 83, 554-627

8 Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 48-58.

9 Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychological inquiry, 11(4), 319-338.