By: Jeff Kosovich and Stephanie Wormington

Many times, organizations measure the impact of leadership development in terms of how it affects their bottom line. However, it is not always clear how these leadership development programs give rise to positive organizational impacts. In this post, we focus on a critical but often overlooked element of professional development: leader identity.

What is Leader Identity, and Why Does it Matter?

So often when people talk about their professional goals and aspirations, the conversation focuses on what they want to do. Do you want to make a six-figure (or seven-figure) salary? Do you want to make a difference in the world? Have time to take care of your family while still maintaining a successful career? Inspire others to succeed? Instead of focusing solely on what you want to do in your career, another important question you can ask yourself is who do you want to be? Think about how you would respond to this question. Is “be a leader” part of your ideal professional future?

Leader identity refers to how someone views him or herself and how they want others to view them. Whether someone currently holds a leadership position or aspires to be a leader in the future, seeing themselves as a leader is a critical part of their professional identity. Considering leader identity shifts the focus from what employees want to do to who they want to be.

When does leader identity begin to form, and how does it change over time? How common is it for young people to see themselves as a leader? What factors contribute to whether someone develops an identity as a leader? Through our work with leaders across their educational and professional trajectories, we have gleaned insights about what it means for individuals to explore, form, and express their leader identities. Below, we share insights from young people in non-profits, K-12 schools, and other youth development organizations about how their identities as leaders developed and influence their work.

Insight 1: Forming your Leader Identity Starts Early, and can be a Bumpy Road for K-12 Students

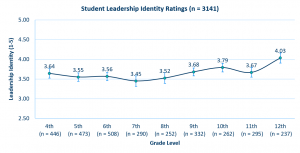

Leader identity can begin to develop before an employee ever steps into the workplace. To learn more about how and when leader identity develops, we collected response from thousands of U.S. K-12 students using the Leadership Indicator for Students tool. The graph below represents the extent to which these students saw themselves as leaders (measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree). Based on responses from 3,141 students in grades 4 through 12, we identified interesting changes in leader identity across time. For example, leader identity does not necessarily follow a linear path. Instead, overall patterns suggest that leader identity begins declining overall as students enter middle school (6th-8th grade) before rising again in high school (starting in 9th grade).

These results align with extensive research suggesting that students experience myriad physical, social, and environmental changes during the middle school years.7,11 During that time, they may experience declines in motivation and engagement2,12 and increases in anxiety or stress8,10 as they become increasingly aware of the world around them.1

These results align with extensive research suggesting that students experience myriad physical, social, and environmental changes during the middle school years.7,11 During that time, they may experience declines in motivation and engagement2,12 and increases in anxiety or stress8,10 as they become increasingly aware of the world around them.1

Research on identity also explores the many changes and explorations that youth undertake during late childhood and adolescence. During adolescence, young people are beginning to explore, challenge, and develop more complex ideas of who they are15,16, including whether they consider themselves to be a leader. High school students may be presented with more opportunities to see themselves in leadership roles, ranging from sports team captain and class president to leading volunteer community projects, which may be associated with greater leader identity.

Responses from K-12 students suggest that leader identity can begin to form long before students enter higher education and the work force. How important is leader identity to young people at the beginning of their professional journeys? Furthermore, are there differences between those who identify as leaders and those who do not?

Insight 2: Many Young Adults See Themselves as Leaders and Know What a Good Leader Looks Like

Our work with several international youth leadership organizations suggests that leader identity continues to be important as young people leave high school and embark on their educational or professional careers. Over the past two years, we have surveyed more than 24,000 Gen Z and Millennials (18 to 30-year-olds) from 63 countries to learn more about how they see their role in global leadership. These studies provide greater insights into how (and how often) young professionals think about leader identity and the implications for their professional careers.

Among the key insights gleaned were that most young people consider themselves to be a leader or want to be one in the future. More than 75% of young people surveyed either currently held a leadership position or aspired to become a leader within the next 5 years. Whether young professionals saw themselves as a leader was associated with the importance they placed on leadership in general. Current and aspiring young leaders were more than twice as likely to say that being a leader was an important part of who they were when compared to young people who did not aspire to a leadership role.4 In other words, being a leader was an important part of current and aspiring leaders’ identity. Beyond understanding how frequently young people saw themselves as leaders, we were also interested in how young professionals define leadership. When asked about what a good leader looks like, young people see leaders as being disciplined, hardworking, creative, capable, and knowledgeable. This indicates that young people identify as leaders and have formed a mental image of how an effective leader operates.

Young people across our studies also provided opinions about what supports and undermines that opportunity to develop leader identity. For example, knowing at least one other young leader was a major differentiator between current leaders and those who did not aspire to be leaders. Country-level and family support that encourages young people to lead also differed greatly between those who did and did not identify as leaders. In each instance, current leaders agreed most strongly that they had support and encouragement, followed by aspiring leaders, followed by those not aspiring to be leaders. One notable example was that 85% of current leaders reported being supported or encouraged by at least 1 adult, compared to 71% of aspiring leaders and only 42% of those not aspiring to be leaders.

Together, responses suggest that many young people identity as current or future leaders, know what a good leader looks like, and view external factors like peer and family support as critical factors for becoming a leader. How might leader identity continue to develop across one’s professional career, and does external support continue to influence leader identity development?

Insight 3: Developing Your Leader Identity Requires Support from Others

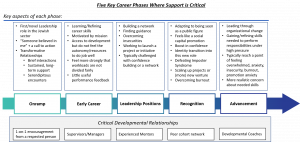

Just because someone holds a leadership role does not guarantee that they identify as a leader. Instead, leader identity often develops and strengthens across the course of a professional career. In a qualitative study conducted by CCL and the Jim Joseph Foundation (unpublished), 83 leaders from Jewish non-profits described their personal leadership journeys in a series of interviews and surveys. From these leaders’ stories, we identified five key career phases of leader identity development: Onramp, Early Career, Leadership Positions, Recognition, and Advancement. Each phase represents an important time for leaders to determine who they are and how they want to lead.

Although every leader’s identity development journey is unique, we identified several shared experiences across individuals. For example, leaders identified critical themes including:

- A growing network of external support

- Learning new skills and building resilience

- Developing confidence

- Becoming more comfortable with one’s identity and role

In other words, gaining confidence and finding support from others were critical factors in developing leader identity. Key across these themes was the importance of receiving support and reinforcement from others. From this work, it is clear that leader identity continues to evolve and develop throughout individuals’ professional careers. Much like developing skills and expertise, understanding who you are as a leader is a continuous journey.

Developing Your Own (and Others’) Leader Identity

The insights shared above suggest that leader identity is important for all ages, develops over time, and can be supported by others. At this point, you might be wondering about how to support your own or others’ leader identity development. Because leadership development is ultimately human development, psychological research has some important lessons to share about developing your and others’ leader identity:

- Know that you can grow: believing that you can become an effective leader is critical for developing your leader identity. Rather than thinking that you’re either born to be a leader or not, be open to the idea that you can improve and grow in your leadership skills.3,6 Allowing yourself to learn over time how to become a leader will help you see yourself as an effective leader. By the same token, emphazing messages of growth for the people you lead or manage can be critical in their own leader identity development.

- Connect becoming a leader to your overarching goals: Connecting your actions to your future goals or a greater purpose (e.g., making the world a better place17) is an effective way to increase your persistence, performance, and learning.5,9,13 Think about how becoming a leader can help you meet your future career or life aspirations as a way to encourage yourself toward developing a leader identity. As a people leader, create space and opportunities for your team members to reflect on their own values and connect them to their work.

- Recognize that support matters: As we heard from leaders at various stages in their professional development, support can be critical for developing leader identity. In particular, feedback, validation, and support systems can play a critical role in whether we see ourselves as leaders and how effective we consider ourselves in leadership roles.14,18 Seek out feedback and ask for support from important people in your personal and professional lives to reinforce your leader identity as it develops. Find ways to also provide that same feedback and support to the people you lead.

As you consider your own identity as a leader—or work with others to support their leader identity development—we encourage you to pause and reflect on the following questions:

- Do you see yourself as a leader right now? Why or why not?

- How important is being a leader to who you are (or your overall identity)? Is it an important part of how you see yourself, or simply a role or position you hold?

- Why do you want to be a leader? What drives you to consider being a leader?

- What experiences, skills, or achievements would support you seeing yourself as a leader?

- Are there actions you might take that would strengthen your leader identity? Can you take any of them right now?

- How can others support you in developing your leader identity?

References

- American Psychological Association. (2018, October 25). APA Stress in America™ Survey: Generation Z stressed about issues in the news but least likely to vote[Press release]. http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2018/10/generation-z-stressed

- Anderman, L. H., & Midgley, C. (1998). Motivation and middle school students. ERIC Journals: New York.

- Caniëls, M. C., Semeijn, J. H., & Renders, I. H. (2018). Mind the mindset! The interaction of proactive personality, transformational leadership and growth mindset for engagement at work. Career Development International, 48-66.

- Center for Creative Leadership & Y20 (2020). Building bridges: Empowering G20 youth to be leaders[White paper]. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

- Choi, Y., Iyengar, S. S., & Ingram, P. (2017). The authenticity challenge: How a value affirmation exercise can engender authentic leadership. In Academy of Management Proceedings(Vol. 2017, No. 1, p. 17318). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological science, 14(3), 481-496.

- Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., & Flanagan, C. (1993). The impact of stage-environment on young adolescents experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48, 90-101.

- Goldstein, S. E., Boxer, P., & Rudolph, E. (2015). Middle school transition stress: Links with academic performance, motivation, and school experiences. Contemporary School Psychology, 19, 21-29.

- Grant, A. M. (2012). Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 458-476.

- Grills-Taquechel, A. E., Norton, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2010). A longitudinal examination of factors predicting anxiety during the transition to middle school. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 23, 493-513.

- Gutman, L. M., & Eccles, J. S. (2007). Stage-environment fit during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 43, 522-537.

- Lepper, M. R., Corpus, J. H., & Iyengar, S. S. (2005). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: Age differences and academic correlates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 184-196.

- Lydon, J. E., & Zanna, M. P. (1990). Commitment in the face of adversity: A value-affirmation approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1040–1047.

- McDonald, M. L., & Westphal, J. D. (2011). My brother’s keeper? CEO identification with the corporate elite, social support among CEOs, and leader effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 661-693.

- Verhoeven, M., Poorthuis, A. M., & Volman, M. (2019). The role of school in adolescents’ identity development. A literature review. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 35-63.

- Wigfield, A., & Wagner, A. L. (2005). Competence, motivation, and identity development during adolescence. Handbook of competence and motivation, 222-239.

- Yeager, D. S., Henderson, M. D., Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., D’Mello, S., Spitzer, B. J., & Duckworth, A. L. (2014). Boring but important: a self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. Journal of personality and social psychology, 107(4), 559–580. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037637

- Zheng, W.and Muir, D. (2015). Embracing leadership: a multi-faceted model of leader identity development. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36, 630-656.