By Sarah Stawiski, Joanne Dias, Douglas Riddle & Sarah Pearsall

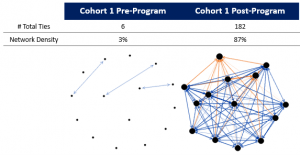

It was a gorgeous fall day in Scottsdale when a group of women healthcare leaders, mostly strangers, began the tentative process of meeting each other, kicking off their fourteen-month journey as Carol Emmott Fellows. Almost a year later in Chicago, as the freezing wind blew in across Lake Michigan, the same leaders came together, ecstatically greeting each other, inquiring about family and work, and interacting as if they had known each other their entire lives. In the course of a year, through their experience in the Fellowship, they had gone from not even knowing one another to forming powerful bonds, just as other cohorts before them had done as well (See Figure A). The Center for Creative Leadership and the Carol Emmott Foundation recently partnered to study the effectiveness of the Fellowship in helping these healthcare leaders develop networks, and the outcomes associated with doing so, with a grant provided by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation.

Figure A. Familiarity before and after the Carol Emmott Fellowship

Note: Blue lines indicate mutual (bidirectional) relationships. Line shading post-program is related to the degree of familiarity reported with darker lines meaning greater familiarity. Density is the extent to which all the possible connections that could exist in a network actually do exist.

About The Carol Emmott Fellowship

Women remain significantly underrepresented in the highest ranks of health leadership. While there are known systemic barriers that perpetuate gender disparity in senior leadership, there are few resources for women to overcome these challenges. The Carol Emmott Fellowship (CEF) is designed to fill this gap. As the CEF program has continued to grow and strengthen in both size and support, the Carol Emmott Foundation has partnered with the Center for Creative Leadership for the current cohorts (CEF4 and CEF5) and onwards. The Carol Emmott Fellowship’s mission is to accelerate the leadership capacity and impact of women leaders in health to enhance fully inclusive gender equity and transform health for all. The program is designed to support women who have already distinguished themselves as rising to a position of responsibility. Program goals include:

- Strengthening Fellows’ unique capabilities, mission, and legacy through self-examination, fellowship, mentorship, and advocacy;

- Developing a community of women working together to transform our organizations and professions; and

- Helping healthcare organizations build more equitable, inclusive, and diverse cultures.

Developing enduring networks is a key mechanism for achieving these goals. Research in the past decade has supported the idea that networks and network perspectives are important for leaders’ career advancement and for accelerating change in systems.1, 2, 3 However, despite the documented value of networks, other research supports the notion that women’s professional networks are often less powerful and effective than are men’s4. Practice and research also support the importance of building networks in development programs to increase a program’s impact by providing continuous support for participants and by disseminating knowledge and skills beyond the participants to other areas of the network5. The development of networks was the key aspect of the program we wanted to better understand through this project.

Advancing gender equity is a complex, long-term goal. The powerful networks formed through the Fellowship are one factor, but more is needed to accelerate change. The Carol Emmott Foundation’s recent efforts to accelerate progress towards this goal include:

- The Foundation has created a complementary program titled The Equity Collaborative that works with health systems to advance gender equity within their workforce.

- Scholarship positions have been created in each cohort to ensure that the Fellowship continues to diversify the pool from which Fellows are selected.

- The Class of 2020 established the Fellows Funding the Future campaign, raising $54,000 in just three months to sponsor a Fellow for the Class of 2022.6

- The programmatic components of the Fellowship include opportunities for Fellows to further diversify their networks by connecting them with thought leaders, writers, policy makers, and national leaders within the healthcare field.

Research Methods

Data were collected from December 2020 to April 2021 and are summarized in the table below.

| Method | People Surveyed | Response Rates |

| Within-Cohort Networks survey | First and third cohorts of CEF | 87% response rate (n=13) for Cohort 1 78% response rate (n=14) for Cohort 3 |

| Extended Networks Survey | People outside of the cohorts that the Fellows nominated because they had developed significant relationships with them during the Fellowship | 50% responses rate (n=17) |

Key Insights

Insight 1: The Fellowship is effectively building networks within and outside of Fellows’ immediate cohorts.

In fact, when asked to compare the Fellowship to all the various ways they have been able to develop networks, the Fellowship is rated as better than or among the best ways that Fellows have developed impactful networks throughout their careers.

Insight 2: Networks are sustained over time.

Only 12% of the respondents from the Extended Network (outside their immediate cohort) indicated they had not stayed in contact with the Fellows. Some relationships were initiated five years ago, indicating that the networks developed are enduring.

Insight 3: The within-cohort and extended networks are valuable in multiple ways.

The Fellows reported that they leveraged their networks in several ways, including sharing information with one another, encouragement and emotional support, and career advancement. Of these outcomes, career advancement had the lowest density for both cohorts, meaning that fewer Fellows were receiving and/or providing career advancement support than they were interacting in other ways.

Interestingly, while the direct support with career advancement may have been less frequent, there is evidence that these Fellows are supporting one another’s careers in important ways. For example, in both cohorts, 85% of the Fellows report that their satisfaction with their careers in healthcare had improved or significantly improved as a result of their within-cohort relationships. Another example is that 75% of cohort 1 Fellows and 85% of cohort 3 Fellows reported improvement in their own national visibility as a result of these relationships

Insight 4: The Fellows helped one another through the COVID-19 pandemic by sharing information specifically related to their organizations’ COVID-19 response.

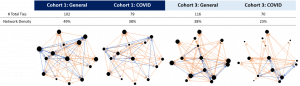

The COVID networks (COVID) were not as dense as general information sharing (General), meaning there was relatively less of this support. However, this type of collaboration and support was happening within both cohorts (Figure B).

Figure B. General information-sharing and COVID-specific support for Cohorts 1 and 3.

Note: Blue lines indicate mutual (bidirectional) relationships. Dot size is relative to the number of people reporting to receive advice or support from that individual.

Insight 5: More distal outcomes such as advancing gender equity and advancing organizational objectives were less impacted than individual outcomes.

This is to be expected in that these outcomes go well beyond impact on one individual in the program. These outcomes require time and are influenced by multiple factors. It is encouraging that some Fellows do see their relationships contributing to these outcomes.

What does this mean:

For advancing gender equity. The results of this research provide clear evidence that networks are about more than just creating new friendships. Oftentimes, peer and professional relationships provided the additional benefit of sharing information that helped the women navigate challenges they faced in their organizations and their responses to a global pandemic, all which can directly or indirectly contribute to career advancement. Additionally, it was the relationships with the Extended Network that seemed to be particularly helpful for career advancement. Those in the Extended Network tended to be very senior level leaders in healthcare and were able to connect the Fellows with opportunities. Both types of relationships (peer and those with more visibility or seniority) are critical for women to advance.

For applicability to other leadership development initiatives. We cannot underestimate the power of the relationships that can be formed in a cohort-based leadership development program. This is applicable not just for women, and not just in healthcare contexts. In many programs, the intimate sense of community formed by participants is seen as a pleasant side-effect. This study adds to the growing awareness among researchers and leadership development professionals that the creation of strong, extensive networks should be a central objective of leadership development design, particularly for marginalized groups.

For networks’ role in supporting and retaining women leaders in healthcare. The within-cohort networks were particularly powerful in providing emotional support and encouragement. And both within-cohort and Extended Networks had a positive impact on these leaders’ job engagement and career satisfaction. Some of the comments provided in the survey pointed to an improvement in resilience and wellbeing as a result of these networks. This has tremendous implications for preventing burnout among senior women leaders in healthcare.

In the words of one of the Fellows who participated in the program, “The energy from the group propels me to cope, use my voice, have bravery and confidence, and the courage to pave a way forward for other women.” The Fellowship is developing a diverse community of remarkable women leaders, and together they can have a tremendously positive impact on gender equity in healthcare organizations.

References

1 Cullen, K., Palus, C., & Appaneal, C. (2014). Developing network perspective: Understanding the basics of social networks and their role in leadership [White paper]. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership. https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.2014.1019

2 Burt, R.S. (2013). Social Network Analysis: Foundations and Frontiers on Advantage. Annual Review of Psychology, 64: 527-547. (retrieved 10 April 2020 pre-print from https://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/ronald.burt/research/files/SNA.pdf

3 Burt, R.S. (2019). Social networks and Creativity. (working paper in press) retrieved 10 April 2020 from https://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/ronald.burt/research/files/SNC.pdf

4 Ely, R. J. (1994). The effects of organizational demographics and social identity on relationships among professional women. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 203-238

5 Cullen-Lester, K., Woehler, M.L., & Willburn, P. (2016). Network-Based Leadership Development: A Guiding Framework and Resources for Management Educators. Journal of Management Education, 1-38.

6 Futch Ehrlich, V.A., & Newlon, B.P. (2021). Designing for Networked Leadership: Shifting from “What?” to “How?” Report to the Jim Joseph Foundation.

7 Carol Emmott Foundation (2020). Annual Report 2020. Retrieved at https://carolemmottfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/CEFAnnualReport2020.pdf

Joanne Dias is a Leadership Solutions Partner at the Center for Creative Leadership who focuses on global leadership development with a particular emphasis on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.

Douglas Riddle is a consulting psychologist who serves as Curriculum Director for the Carol Emmott Foundation and a senior fellow at the Center for Creative Leadership.