By: Marcia Alesan Dawkins and Ramya Balakrishnan

Based on our research, the answer is they can be. Corporate statements tell us about organizations’ readiness to address imbalanced systems. They also serve as benchmarks for understanding stakeholder experiences and diversity metrics.

On May 25, 2020, virtually anyone with access to social media experienced “The Age of Black Death.” Collective well-being suffered as we watched Black American lives like George Floyd’s and Breonna Taylor’s ending tragically. Many found it increasingly difficult to go on, both personally and professionally.

In response to these difficult experiences, today’s leaders are starting new and different conversations across their organizations about systemic oppression and accountability. Leaders are sharing reactions directly in public statements, acknowledging public benefits of diversity and the need for collective accountability when it comes to equity and inclusion. At the same time the public is using social media and protest to hold organizations accountable for inequitable practices. Due to their public nature, corporate statements are both a starting point for examining organizations’ commitments to equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) and a baseline against which they can measure progress.

Understanding the statements

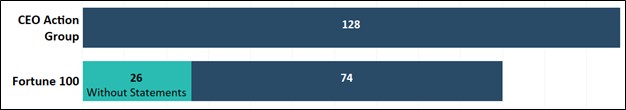

We confirmed and analyzed 202 available statements from 228 Fortune 100 and CEO Action Network for Diversity and Inclusion1 member organizations. Our sample count is visualized in the image below. To account for the 26 organizations that did not issue statements, we also consider silence a response. When organizations can speak out and do not, they are choosing to accept the way things are. History tells us that stakeholders take note of these choices. As Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” Consequently, there are no singular or neutral positions on systemic oppression.

Figure 1: EDI Statement Sample Count

Figure 1: EDI Statement Sample Count

For organizations that responded with statements, each response presents story about what led to the shared perception of “The Age of Black Death” as both a moment of trauma and an opportunity for transformation. Each story is made up of themes, including motivations for action (drivers for behavior), personas (leadership character traits), and outcomes (optimistic EDI endings).

Figure 2: Motivations, Personas, and Outcomes Themes in the Statements

Figure 2: Motivations, Personas, and Outcomes Themes in the Statements

As examples: “responding to trauma” of collective citizen witnessing is a motivation theme that drives organizational action; “we are heroes,” is a persona theme that communicates character traits necessary for engaging in successful, systemic EDI work (i.e., resilience, victory, ability to recognize and respond to villains); and, “EDI goals and metrics” is an outcome theme that sets the scene for success.

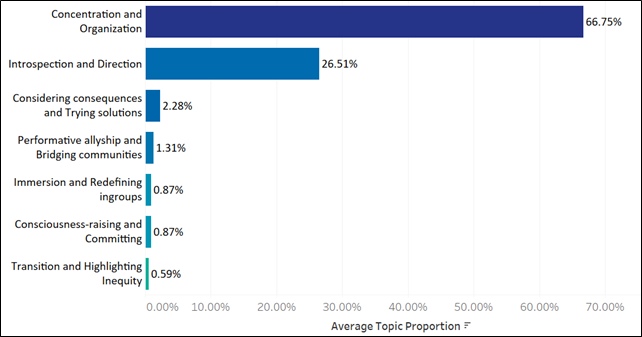

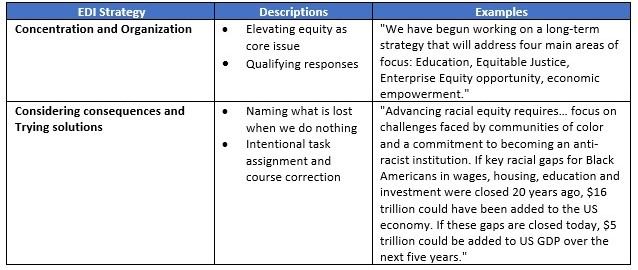

Each corporate statement communicates an understanding of what has led to the shared perception of “The Age of Black Death” as both a moment of trauma and an opportunity for transformation. These understandings, taken together, revealed seven distinct EDI strategies (shown below).

Figure 3: Topic Proportion of EDI Strategies in the Statements

Figure 3: Topic Proportion of EDI Strategies in the Statements

Nearly 70% of statements reflected an EDI strategy of “Concentration and Organization” or “Considering Consequences and Trying Solutions.”

These strategies rely on diagnostics such as data collection and organizational development, suggesting that most organizations are adapting their approach to EDI from one that emphasizes personal development to one that actively works toward systemic change. Terms like “working,” “commitment,” “focus,” and “requires” reveal the persona of senior leadership as committed to policies that address inequities. The role of senior leadership is to demonstrate commitment to policies that address inequities and ensure equitable policies and procedures are in place. Statements indicate that these organizations are actively aligning and socializing EDI strategy with key stakeholders to ensure actions are taken and outcomes are met.

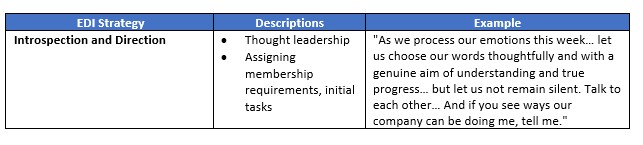

Compare the above to an example that embodies the “Introspection and Direction” strategy, which represents 26.51% of the statements analyzed.

“Introspection and Direction” relies more on personal development and less on the roles of context and systemic change, suggesting that the organization is in the early formation of an EDI strategy that has not yet been aligned to talent or business strategy. In other words, change belongs with the individual. Based on the “Introspection and Direction” excerpt above, we might say the organization is learning how to distinguish symptoms of EDI-oriented pain from root causes. The persona of senior leadership is to model self-reflection and thought leadership (“process,” “understanding,” “progress”). As such, senior leadership is cast as open-minded and empathetic (“genuine”). Stakeholders are instructed to demonstrate EDI commitment through open dialogue and sharing the need for an EDI strategy even though nothing has yet been developed.

“Introspection and Direction” relies more on personal development and less on the roles of context and systemic change, suggesting that the organization is in the early formation of an EDI strategy that has not yet been aligned to talent or business strategy. In other words, change belongs with the individual. Based on the “Introspection and Direction” excerpt above, we might say the organization is learning how to distinguish symptoms of EDI-oriented pain from root causes. The persona of senior leadership is to model self-reflection and thought leadership (“process,” “understanding,” “progress”). As such, senior leadership is cast as open-minded and empathetic (“genuine”). Stakeholders are instructed to demonstrate EDI commitment through open dialogue and sharing the need for an EDI strategy even though nothing has yet been developed.

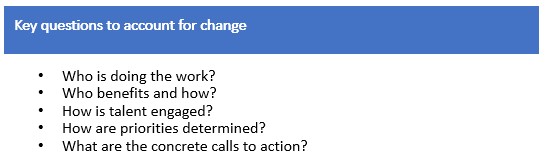

To meaningfully account for progress in organizations’ EDI work, it is necessary to clearly distinguishing strategic priority setting from strategic priority implementation. Leaders can ask questions to better understand the resources dedicated to and anxieties inherent in changing everyday actions, internal operations, and external commitments. Leaders can ask the following questions.

Posing these questions does not mean we think organizations aren’t fulfilling their commitments. Rather, we are suggesting that more information is needed. After publicly announcing their EDI efforts, organizations and their leadership should sustain their efforts to attract and retain underrepresented talent and avoid weakening their efforts. To get there, EDI strategies should be updated to include answers that account for long-term culture change.

Posing these questions does not mean we think organizations aren’t fulfilling their commitments. Rather, we are suggesting that more information is needed. After publicly announcing their EDI efforts, organizations and their leadership should sustain their efforts to attract and retain underrepresented talent and avoid weakening their efforts. To get there, EDI strategies should be updated to include answers that account for long-term culture change.

Where can leaders go from here?

Sustaining corporate commitments to EDI requires a willingness to innovate and to solve problems that have not yet been solved by publishing statements alone. To make progress leaders should:

Reveal relevant opportunities. Acknowledge it is no longer possible to avoid systemic oppression or publicly reconcile contradictions between cosmetic diversity and substantive change. Acknowledge how and why systemic exclusion is a problem that affects society and business. Define commitment for your organization and to your employees and teams specifically. Identify 2-3 strategic actions to drive change. Typical starter actions include representation reporting, metrics, listening sessions, and raising awareness of EDI efforts.

Move beyond a “view from the top”. Leaders can examine employee reviews on sites like Glassdoor, which describe specific issues employees are encountering along the hiring path from recruitment to retention and promotion and exit. Reviews contain important insights about how employees work within formal and informal networks, about how diverse and inclusive the organization’s culture is, and about systematic advantages and disadvantages associated with employment and performance. Typical commitments expressed in reviews include: diverse representation, pay equity improvements, progress reports, rewards, relationship roles, and potential impacts of and fears about EDI work.

Embrace a “listen-first” approach. Before announcing EDI efforts publicly, leaders should listen to what their stakeholders are saying about how equity, diversity and inclusion impact their professional and personal lives. Leaders can identify gaps between what their organizations are saying and what they are doing, and where they can turn for guidance and support. Listening first allows leaders to gather important information about problems, progress, conditions, and requirements as well as the capabilities and limitations of resources. For instance, leaders can listen for ways to facilitate equity in professional development, quality employment, and healthcare. This kind of first-hand information can create new knowledge about EDI, improve ability to identify and mitigate bias, and promote collaboration through which organizational leaders and stakeholders bring out the best in one another.

While EDI efforts may seem overwhelming, in-depth understanding of what organizations are saying and doing is necessary for effective leadership. Effective leaders can turn the worlds envisioned in their statements into a reality that embraces the full range of potential across the workforce by investing in change that benefits all people.

References

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y. & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993-1022.

Bormann, E. G. (1983). Symbolic convergence: Organizational communication and culture. In L Putnam,& M.E. Pacanowsky (Eds.), Communication and organizations: An interpretive approach (pp. 99-122). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

[1] CEO Action for Diversity & Inclusion™ is the largest CEO-driven business commitment to advance diversity and inclusion in the workplace. CEO Action was founded on a shared belief that diversity, equity and inclusion is a societal issue, not a competitive one, and that collaboration and bold action from the business community – especially CEOs – is vital to driving change at scale.