By: Katelyn McCoy and Dan Smith

According to the International Coaching Federation’s 2023 Global Coaching Study, coaching in the leadership development space has seen a surge of interest across several industries in recent years. When implemented effectively, coaching initiatives can dramatically improve an organization’s leadership capacity, as well as drive higher levels of employee engagement, well-being, and productivityi. But how does coaching lead to these results?

One way to explore the answer to that question is through the lens of psychological capital.

What is Psychological Capital?

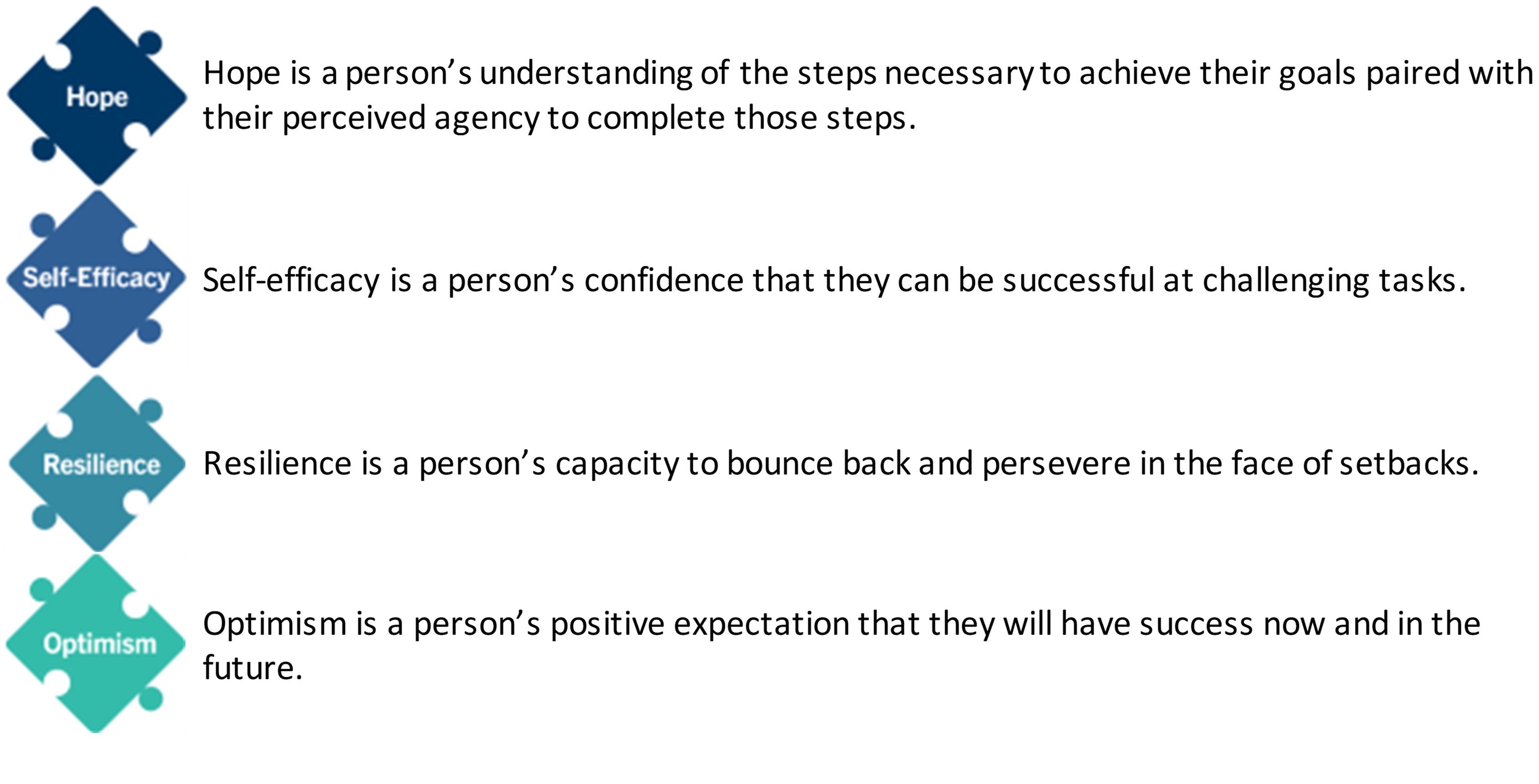

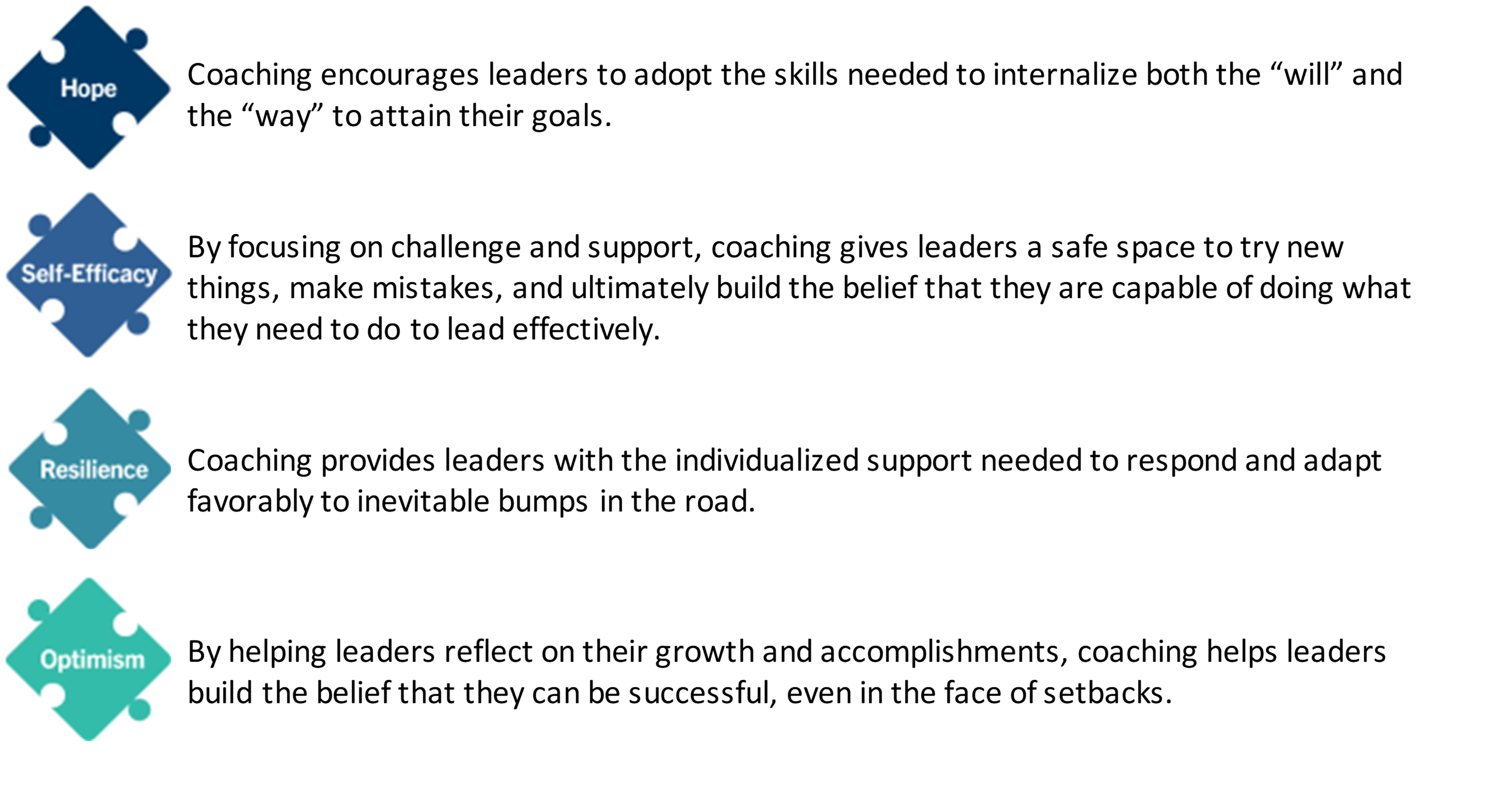

Spotlighted recently in an APA review on the topic, psychological capital (or PsyCap, for short) is an individual’s overall “positive appraisal of circumstances and probability for success based on motivated effort and perseveranceii.” It is a combination of four positive psychological states—hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism—that, when considered all together, are conducive to personal and professional growth. Researchers who study PsyCap utilize specific, measurable definitions for each of these four components:

Over the last several years, a substantial amount of research has highlighted the benefits of PsyCap for positive organizational outcomes. Employees with higher PsyCap are more committed to their organization, perform better, have higher levels of well-being, and experience less burnoutiii. Newer research also suggests that individuals with higher PsyCap display better leadershipiv. In particular, these researchers found that leaders with higher hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism also scored highly on the four key dimensions of authentic leadership: self-awareness, relational transparency, balanced processing, and internalized moral perspective. Authentic leadership has been associated with higher levels of several workplace outcomes, including work engagement, job performance, job satisfaction, commitment, and trustv.

Good Coaching Makes Leaders Better… And PsyCap May Explain Why

The magic that makes leadership coaching effective can be a bit of a “black box”vi. Among coaching providers, a host of formats, practices, content, and models are at play, each of them with their own merits. This supports flexible and fluid coaching designed to meet the needs of the person being coached. Additionally, each leader experiencing coaching has their own motivations, challenges, and goals, and the organizations where those leaders work often have their own intentions for funding a coaching initiative, which can influence the outcomes. All of these variables make it difficult to know whether coaching is really moving the needle in an organization, but a few key aspects of coaching can help us understand why leaders often come away from it feeling transformed.

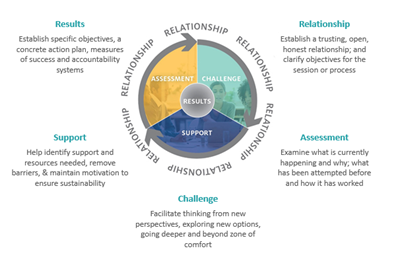

The process of leadership coaching typically involves elements of assessment and self-reflection, perspective-taking, challenge, and support. These elements come together to help leaders set meaningful goals for themselves and, with enough time and support, reach them.

[Image Caption: CCL’s coaches utilize a research-based model called RASCR™ that wraps the one-on-one coaching Relationship around four other elements: Assessment, Challenge, Support, and Results.vii]

Coaching often leads to improvements in leaders’ communication skills, commitment, positive emotions, and self-awareness, all of which help individuals enact more effective leadershipviii. These outcomes either closely align with the underlying principles of PsyCap or with its observed outcomes, particularly positive emotions. Put another way, effective coaching seems to instill in leaders a positive psychological state that’s ripe for development, which likely leads to transformative outcomes down the line.

Psychological Capital is Developmental Jet Fuel

PsyCap can be thought of as a fuel that supports the pursuit of whatever target or outcome an organization cares most about. In the case of leadership development, PsyCap can act as a booster for individual developmental outcomes, as well as a side effect of the development itself, explaining why leadership development initiatives have been shown to produce downstream impacts like improving employee engagement and reducing burnout. In the case of coaching, the one-on-one nature of a coaching relationship is ultimately aimed at personal improvement through shifts in mindset, behavior change, and goal achievement, all of which may give leaders an extra boost of developmental jet fuel, leading to greater long-term effects.

A host of research has shown that increasing leaders’ hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism gives them the fuel they need to foster sustained, positive change in themselves and their teams. Interventions geared at increasing elements of PsyCap, like CCL’s Burn Bright, have been largely successfulix, some in as quick as a few minutesx. While focusing on the positive outcomes of leadership coaching through the lens of PsyCap is fairly new, its utility is clear.

Each component of PsyCap is uniquely beneficial for developing leaders who, on top of learning the skills they’ll need to lead effectively, also need to be able to authentically articulate their visions for the future, usher others through challenges and disruptions, and believe they have what it takes to guide their teams to success. Put together, these components create the perfect fuel for developmental outcomes, and may uncover some of the mystery of what makes coaching so effective for leaders. Essentially, coaching provides the support needed to foster sustainable change and may even have the added benefit of boosting the effects of other leadership development efforts by improving leader PsyCap.

Each component of PsyCap is uniquely beneficial for developing leaders who, on top of learning the skills they’ll need to lead effectively, also need to be able to authentically articulate their visions for the future, usher others through challenges and disruptions, and believe they have what it takes to guide their teams to success. Put together, these components create the perfect fuel for developmental outcomes, and may uncover some of the mystery of what makes coaching so effective for leaders. Essentially, coaching provides the support needed to foster sustainable change and may even have the added benefit of boosting the effects of other leadership development efforts by improving leader PsyCap.

And the best part? It’s contagious.

Not only does PsyCap relate to several positive workplace outcomes, but it can also spread organically from leaders to their team membersxi. Therefore, coaching that improves PsyCap for leaders can also lead to psychological growth throughout the leaders’ networks, resulting in a greater capacity for productivity and well-being across the organization. This means giving even one leader access to good coaching could potentially have far-reaching effects.

Decades of research on the underlying components of PsyCapxii, as well as a recent field experiment by Andrea Fontes and Silvia Dello Russoxiii, demonstrate that organizations who want to optimize formal coaching or coaching behaviors to improve employees’ PsyCap should make goal-setting a core part of their coaching activities. For most professional coaches, this is a no-brainer, as the research on goal-setting shows that leaders’ successful experiences related to their goals positively impacts their self-efficacy. As well, striving towards meaningful goals with sufficient support can increase leaders’ hope, resilience, and optimism. Fontes and Dello Russo’s study provided evidence that coaching based on the popular, goal-focused GROW modelxiv increased participants’ PsyCap and, by doing so, improved their job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Coaches can maximize each component of PsyCap for their leaders by leveraging their role as an additional support to help them problem-solve, chart new paths in the face of resistance, accurately appraise their own situations, and practice good coping strategies.

The research is clear – developing psychological capital drives better leadership and amplifies positive outcomes. It’s time to leverage coaching as a strategic investment in your human capital.

- Invest in personalized coaching to build hope, self-efficiency, resilience, and optimism in leaders. Leading is hard work, and increasingly even the best leaders are finding themselves feeling unsupported and burnt out. The research on PsyCap shows that investing in solutions that increase leaders’ hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism could give them the fuel they need to press on, as long as it’s accompanied by solutions for helping them feel more supported and reducing the factors that led to burnout in the first place.

- Design inclusive leadership development focused on psychological needs and support systems. World events, organizational changes, and personal situations can all contribute differentially to leaders’ PsyCap. To design an inclusive leadership development initiative, be mindful that leaders may not all have the same level of readiness. A solution that helps everyone feel supported and reinvigorated will be more effective for more people than one that feels like another organizational challenge or chore.

- Leverage mentorship and employee resource groups to strengthen PsyCap organization-wide. Developing leaders is a great way to produce far-reaching effects, and not every employee in an organization holds a formal leadership position. Aside from being mindful about how you design or choose your leadership development initiatives, consider other options for directly improving the PsyCap of all your employees. These may include employee resource groups (ERGs) that help employees feel connected and capable of taking on workplace challenges or mentorship programs that help them build the hope and optimism they feel about their careers.

The opportunity to enhance leaders’ psychological capital through coaching is too important to miss. Developing the fuel of hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism in your leaders will equip them to lead authentically, drive change effectively, and multiply positive impacts across your organization. By investing strategically in personalized coaching and inclusive leadership development focused on meeting psychological needs, you can build the vital resources your leaders and organization need to excel now and into the future. Don’t leave this transformational opportunity untouched – take action today to propel your leaders and organization to new heights.

[i] Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., & Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.837499

[ii] Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541-572.

[iii] Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(2), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20070; Choi, Y., & Lee, D. (2014). Psychological capital, Big Five traits, and employee outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(2), 122–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2012-0193; Paek, S., Schuckert, M., Kim, T. T., & Lee, G. (2015). Why is hospitality employees’ psychological capital important? The effects of psychological capital on work engagement and employee morale. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 50, 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.07.001

[iv] Petersen, K., & Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2018). The “left side” of authentic leadership: Contributions of climate and psychological capital. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 39(3), 436–452. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-06-2017-0171

[v] Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., & Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 44(2), 501–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316665461

[vi] Patrick, S. K., Rogers, L. K., Goldring, E., Neumerski, C. M., & Robinson, V. (2021). Opening the black box of leadership coaching: An examination of coaching behaviors. Journal of Educational Administration, 59(5), 549–563. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-08-2020-0168

[vii] Frankovelgia, C. C., & Riddle, D. D. (2010). Leadership coaching. In The Center for Creative Leadership Handook of Leadership Development (pp. 125–146). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

[viii] Athanasopoulou, A., & Dopson, S. (2018). A systematic review of executive coaching outcomes: Is it the journey or the destination that matters the most? The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.11.004

[ix] Lupșa, D., Vîrga, D., Maricuțoiu, L. P., & Rusu, A. (2020). Increasing psychological capital: A pre‐registered meta‐analysis of controlled interventions. Applied Psychology, 69(4), 1506–1556. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12219

[x] Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S. M., & Combs, G. M. (2006). Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(3), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.373

[xi] Story, J. S. P., Youssef, C. M., Luthans, F., Barbuto, J. E., & Bovaird, J. (2013). Contagion effect of global leaders’ positive psychological capital on followers: Does distance and quality of relationship matter? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(13), 2534–2553. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.744338

[xii] Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behaviour. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 23, 695–706.

[xiii] Fontes, A., & Dello Russo, S. (2021). An Experimental Field Study on the Effects of Coaching: The Mediating Role of Psychological Capital. Applied Psychology, 70(2), 459–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12260

[xiv] Whitmore, J. (2003). Coaching for performance, growing people, performance and purpose. Boston, MA: Nicholas Brealey.