By Katya Fernandez

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a significant toll on individuals’ physical, mental, emotional, and social well-being, both personally and professionally. For many, this disruption greatly impacted the workplace, with organizations shifting to remote work, implementing new safety protocols, implementing reduced salaries, furloughs, and layoffs due to revenue losses, and creating new norms and expectations during a period of enormous uncertainty. Any and all of these disruptions can lead to a host of related effects for employees, including stress and anxiety about the pandemic itself.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have explored the psychological impact of the pandemic on individuals1. After witnessing the significant challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic firsthand, we wanted to explore how to support leaders in such uncertain times. We conducted a study2 in which we explored (a) the relations between COVID-related stress and three important outcomes for leaders (burnout, job satisfaction, and overall well-being), (b) whether resilience, gratitude, and intolerance of ambiguity might play a role in alleviating COVID-related stress, and (c) how background characteristics of participants and work-related changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic related to our topics of interest.

What is COVID-related Stress?

While most past studies on stress and leadership have focused on various types of stress (e.g., general stress, work-related stress), we specifically focused on COVID-related stress in leaders. In trying to measure how much COVID-related stress leaders were experiencing, we assessed three specific components3,4: (a) compulsive checking and reassurance seeking behaviors regarding COVID-19 worries (e.g., checking your body for signs of infection), (b) experiencing traumatic stress responses to COVID-19 (e.g., having difficulty concentrating because you keep thinking about the virus), and (c) feeling threatened by the virus (e.g., worrying that you or people you love will get sick from the virus).

Why Resilience, Gratitude, and Intolerance of Ambiguity?

Resilience, which we define as “responding adaptively to challenges,” has an extensive history as a potentially effective way of coping with stress and burnout. We selected gratitude, or being thankful for what you have, because it is a key resilience practice during times of crisis5,6,7 and has been found to be related to many forms of well-being, including higher self-esteem, boosted physical health, better sleep, and greater life satisfaction8,9. Finally, research has found that intolerance of ambiguity—an individual difference that reflects how accepting people are of uncertainty—is a risk factor for a variety of maladaptive psychological outcomes, such as stress10; this finding, coupled with the enormous uncertainty that accompanied the arrival and course of the COVID-19 pandemic, made intolerance of ambiguity an ideal candidate for examining potential relations to COVID-related stress.

Key Insights

Insight 1: COVID-related Stress is Taking a Toll on Leaders

Our first insight was that COVID-related stress had a negative effect on leaders; more specifically, COVID-related stress was related to lower overall job satisfaction and well-being and higher levels of burnout. Additionally, COVID-related stress was significantly related to lower resilience and gratitude and higher intolerance of ambiguity. These results make it clear that the COVID-19 pandemic is impacting workplace well-being. Leaders who report feeling a lot of COVID-related stress, such as worrying about getting the virus or feeling unable to focus due to the pandemic, are suffering more than others.

Insight 2: The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed How, When, and Where We Work

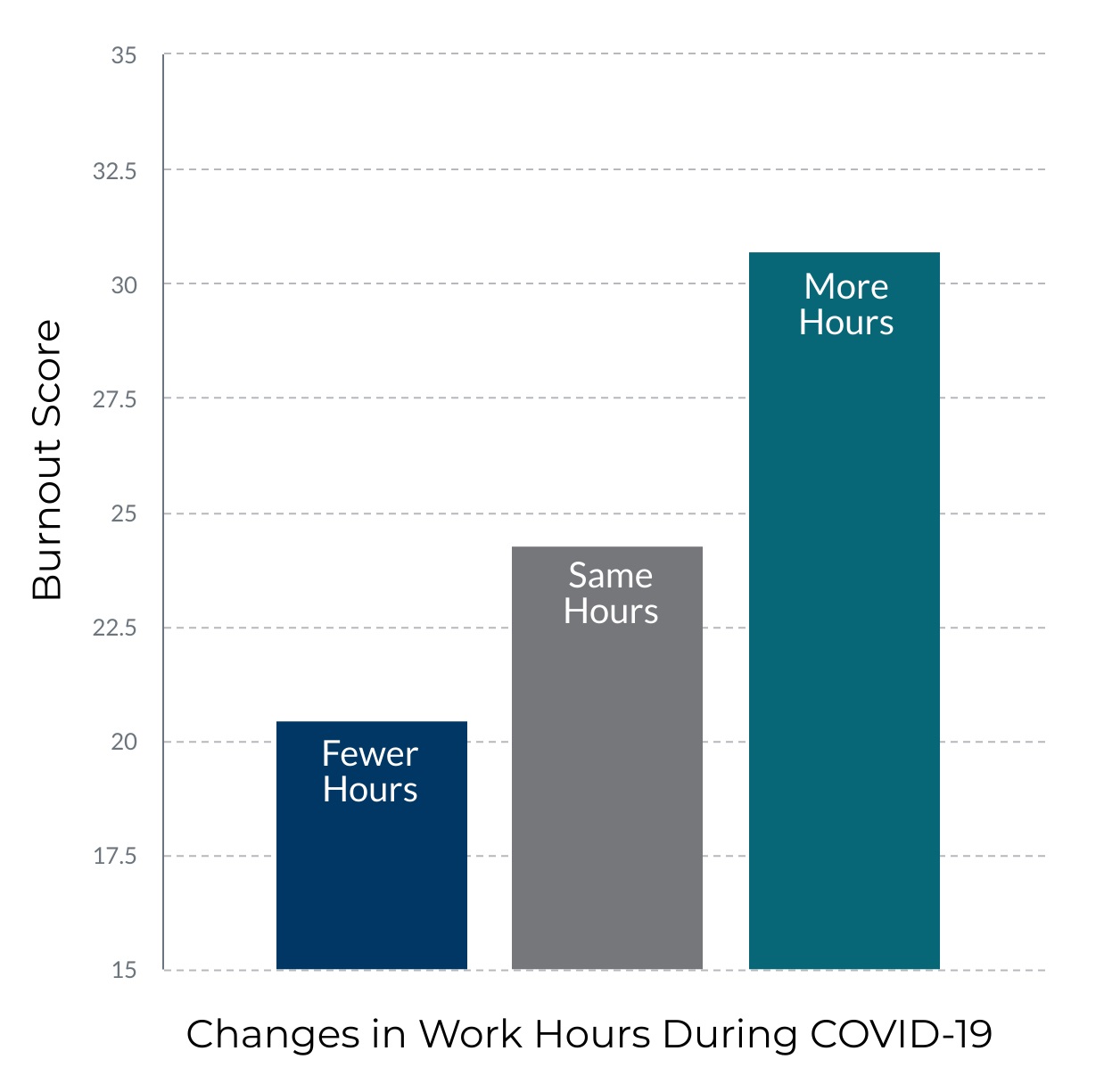

Many leaders also shared that their work and workplace have changed during the pandemic. In particular, we examined three workplace changes: remote work, company furloughs, and work hours. We found that:

- Those who were working remotely reported higher levels of gratitude compared to those not working remotely.

- Those who reported their organizations have furloughed employees reported lower job satisfaction compared to those in organizations with no furloughs.

- Those who reported working more hours since the COVID-19 pandemic began reported more burnout compared to those reporting working about the same or fewer hours.

Note: Higher burnout scores indicate higher levels of self-reported burnout.

Taken together, it appears as though the shift to remote work may have had some positive effects (in terms of gratitude), while the other trends of increased work hours and furloughs have been potentially more harmful. We encourage organizations and leaders to consider these findings as they plan for the future of the workplace post-COVID-19 pandemic. For example, leaders and organizations may want to consider extending remote and flexible working options even after employees are able to gather together in person. Making such options available may offer employees more opportunities for selecting a work environment that best fits their needs.

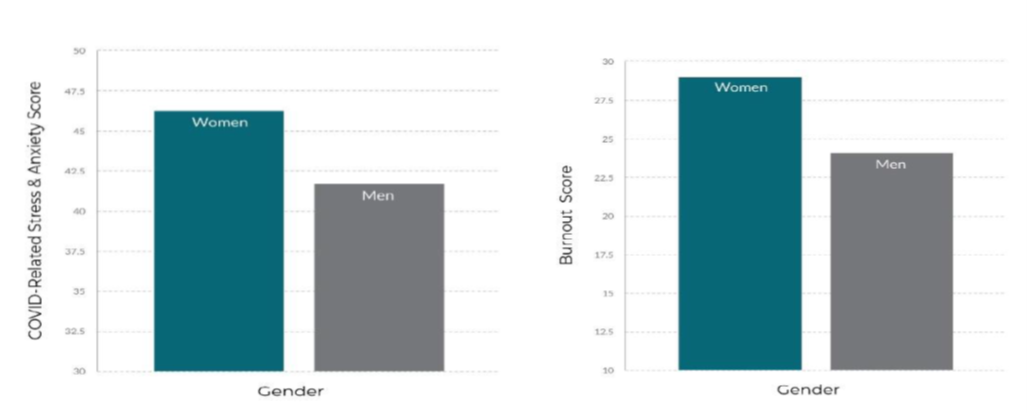

Insight 3: The COVID-19 Pandemic has Disproportionately Impacted Women

Compared to men, women reported higher levels of COVID-related stress and burnout and lower levels of resilience and well-being. One possible reason for this finding may be related to housework and childcare outside of work: McKinsey & Company11 found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, mothers are more than three times as likely as fathers to be responsible for most of the housework and caregiving. The housework and caregiving itself may have become more intense throughout the course of the pandemic (e.g., having to cook or clean more if family members spend more time at home, having to homeschool children on top of their usual responsibilities). We encourage leaders and organizations to be aware that women are being disproportionally impacted during this pandemic and take steps to ensure they retain their female talent. If you have direct reports who are women, discuss with them what would be most helpful. For example, organizations could consider offering women (and all employees) flexibility, time off, and additional support. Some organizations are allowing parents to use family and medical leave to homeschool their children during this difficult time. Other organizations are offering free counseling, childcare, or self-care resources.

Note: Higher COVID-related stress and anxiety scores indicate higher levels of self-reported COVID-related stress and anxiety; higher burnout scores indicate higher levels of self-reported burnout.

Insight 4: Older and More Experienced Leaders May Be Coping Better with the Pandemic

We found that older participants in our study experienced lower levels of burnout, higher levels of well-being, and were more comfortable with ambiguity. In terms of leader level, we found that executives, in particular, rated themselves as more tolerant of ambiguity compared to individual contributors. Overall, we interpret this pattern of findings to be an optimistic one, suggesting that wisdom does indeed come from experience and that we may be better able to weather uncertainty overtime. However, the flipside of this finding suggests that younger people and those lower in the organization might be having a harder time dealing with the uncertainty of the pandemic. We encourage leaders and organizations to create opportunities for information and strategy sharing, and support for younger individuals in their organizations, during and after the pandemic.

Insight 5: Leaders Can Cope with COVID-related Stress

Finally, we explored what strategies (resilience, gratitude, and intolerance for ambiguity) might be effective in helping people cope with COVID-related stress. Results suggest that resilience, gratitude, and tolerance for ambiguity can lessen the negative impact of COVID-related stress on job satisfaction and well-being. In other words, when looking at individuals reporting COVID-related stress, those who felt more resilient, more grateful, and/or more tolerant of ambiguity had higher job satisfaction and well-being. For job satisfaction, specifically, each of these three factors (resilience, gratitude and tolerance for ambiguity) completely counteracted the effects of COVID-related stress; once we accounted for them in our analyses, COVID-related stress was no longer related to decreased job satisfaction.

Now What?

Taken together, our insights yield implications for leaders and the actions they can take to decrease the effects of COVID-related stress, especially leaders still facing the COVID-19 pandemic and/or its consequences. Leaders and organizations being open, transparent, and honest about how COVID-related stress can affect people’s lives is an invaluable first step. Second, implementing programming in the workplace that focus on cultivating resilience, gratitude, and tolerance for ambiguity can be useful in helping leaders manage the impact that COVID-related stress is having on burnout, job satisfaction, and well-being. Even once COVID-related stress subsides (e.g., as COVID-19 vaccines become more widely available), new forms of post-pandemic stress may emerge; for instance, readjusting to onsite work if working remotely during the pandemic, rebuilding in-person workplace relationships, balancing virtual and in-person meetings, etc. Resilience practices will continue to remain important in helping leaders cope with new and challenging stressors.

Now is the time to double down on resilience because resilience helps buffer against stress and burnout. Leaders can utilize a variety of resources to focus on cultivating their own resilience (e.g., by engaging with evidence-based resilience practices such as gratitude), and organizations can support leaders in their cultivation of resilience (e.g., by offering resilience programs or resources). To read more about research-based ways to cultivate resilience and gratitude and cope with ambiguity, please review CCL’s article5 Building Leadership Resilience: The CORE Framework, focused on introducing the CORE framework and/or the upcoming book focused on introducing and expanding on the CORE framework releasing in 2021 by Marian Ruderman, Cathleen Clerkin, and Katya Fernandez.

References

1Gallagher, M. W., Zvolensky, M. J., Long, L. J., Rogers, A. H., & Garey, L. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 experiences and associated stress on anxiety, depression, and functional impairment in American adults. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1–9. Advance online publication.

2Fernandez, K. C., & Clerkin, C. (2021). Leading through COVID-19: The impact of pandemic stress and what leaders can do about it [Research Insights paper]. Center for Creative Leadership. https://cclinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/leading-through-covid19.pdf

3Conway, L. G., III, Woodard, S. R., & Zubrod, A. (2020, April 7). Social psychological measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus Perceived Threat, Government Response, Impacts, and Experiences Questionnaires. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z2x9a

4Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Fergus, T. A., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2020). Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 72, 102232.

5Fernandez, K. C., Clerkin, C., & Ruderman, M. N. (2020). Building leadership resilience: The CORE framework [Research Insights paper]. Center for Creative Leadership. https://cclinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/researchinsights_1220_rev1.pdf

6Lies, J., Mellor, D., & Hong, R.Y. (2014). Gratitude and personal functioning among earthquake survivors in Indonesia. Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(4), 295-305.

7Vieselmeyer, J., Holguin, J., & Mezulis, A. (2017). The role of resilience and gratitude in posttraumatic stress and growth following a campus shooting. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(1), 62–69.

8Jackowska, M., Brown, J., Ronaldson, A., & Steptoe, A. (2016). The impact of a brief gratitude intervention on subjective well-being, biology and sleep. Journal of health psychology, 21(10), 2207-2217.

9Wood, A. M., Joseph, S., & Maltby, J. (2009). Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the Big Five facets. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(4), 443-447.

10Bardeen, J. R., Fergus, T. A., & Orcutt, H. K. (2017). Examining the specific dimensions of distress tolerance that prospectively predict perceived stress. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(3), 211-223.

11McKinsey & Company. (2020). Women in the workplace: Corporate American is at a critical crossroads. https://wiw-report.s3.amazonaws.com/Women_in_the_Workplace_2020.pdf